27 Aug Nonsense

by Anushka Ravishankar

Anushka Ravishankar, long time author at Tara Books, is a renowned writer of some really silly verse. Her work originates in many ways: she has written to pictures, and artists have returned the favour by drawing to her rollicking text. A Rooster for a Pet?, though, has an entirely different origin: the book was inspired by the film Tungrus by Rishi Chandna, about a Mumbai resident who decided to adopt a rooster. Having seen the movie, she decided a book cannot be far behind.

On the occasion of the book’s publication, we invited her to write a note on her adventures in nonsense (and sense).

I did not discover nonsense so much as recognise it with a shout of joy when I was almost twenty years old. What a waste of two decades! Of course, I had read nonsense as a child. I’d read the wickedly funny poems in the Alice books by Lewis Carroll and I knew some of Edward Lear’s gently silly poems and limericks. But I had no idea that nonsense was a respected literary genre. (Well, sort of respected.)

But one lonely summer, when I spent many days at a British Council library, I read a book with an eclectic collection of nonsense verse and prose, and I was hooked! I began to write nonsense verse in my mathematics notebooks (especially when exams were looming) and the abandoning of logic and sense afforded me many hours of liberation from the rigours of mathematical reasoning.

However, it was a lonesome business, this writing of nonsense. When I showed what I’d written to friends and relatives, the reaction varied from “Enh?” to “What on earth is this?” to “Why don’t you write something sensible for a change?” I retired, hurt, and wrote deep and awful poetry, which, thankfully, no one ever read.

Early days: Anushka at Tara

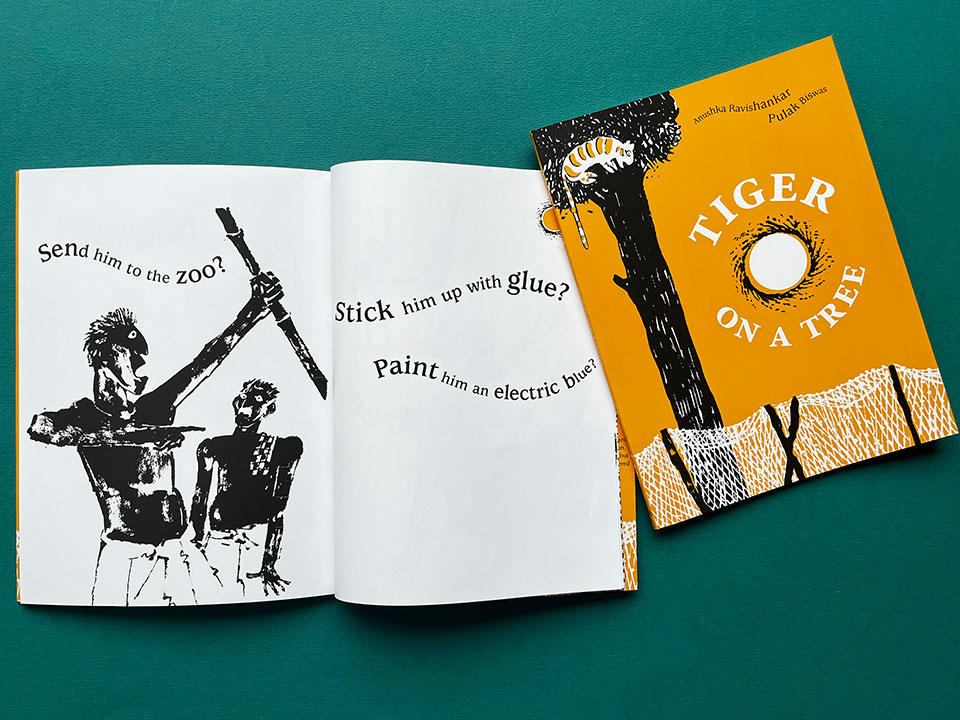

In 1996, I joined Tara as an editor. One of my earliest assignments was to write the text to a story which had been told pictorially by the much-beloved illustrator, Pulak Biswas. He had been inspired by a partly true story about a tiger that strayed into a village. I looked at the illustrations and my first reaction was that it really did not need words. The illustrations already told the whole story. So what was I to do? I began to write, trying to keep the text at a tangent to the pictures. While the whole poem wasn’t nonsensical, I wrote some very absurd lines — for example, these ones, which have the villagers pondering over what to do with the beast:

I can honestly say that no other editors would have allowed those utterly nonsensical lines to stay in the middle of what was a fairly straightforward narrative. Tiger on a Tree was my first book, and it set me firmly on the path to nonsense.

I followed this one up with another — Catch that Crocodile. Again, based on a partly true story about a crocodile that was found in a small town’s water lines. This time, I wrote the story first, in detailed prose. After Pulak drew the pictures, I deleted the text and rewrote it in verse. There was a lot of nonsense in this text too — like this description of a doctor who tries to inject the animal to sleep:

Catch that Crocodile

Once again, Tara’s editors let these lines be, and actually egged me on. At Tara, I had finally found my comrades in absurdity! All of us revelled (and continue to revel) in the silly, and the unlikely. What strikes me is that we created the book together. We traded lines, and nonsense, sometimes literally rolling on the floor laughing at our own absurdity (and I do mean literally — we were working on a mat, so we didn’t fall off our chairs). Through this process, the old ways of looking at a book, as essentially the writer’s, were subverted and the book belonged equally to the illustrator, the writer, the designer and the publisher.

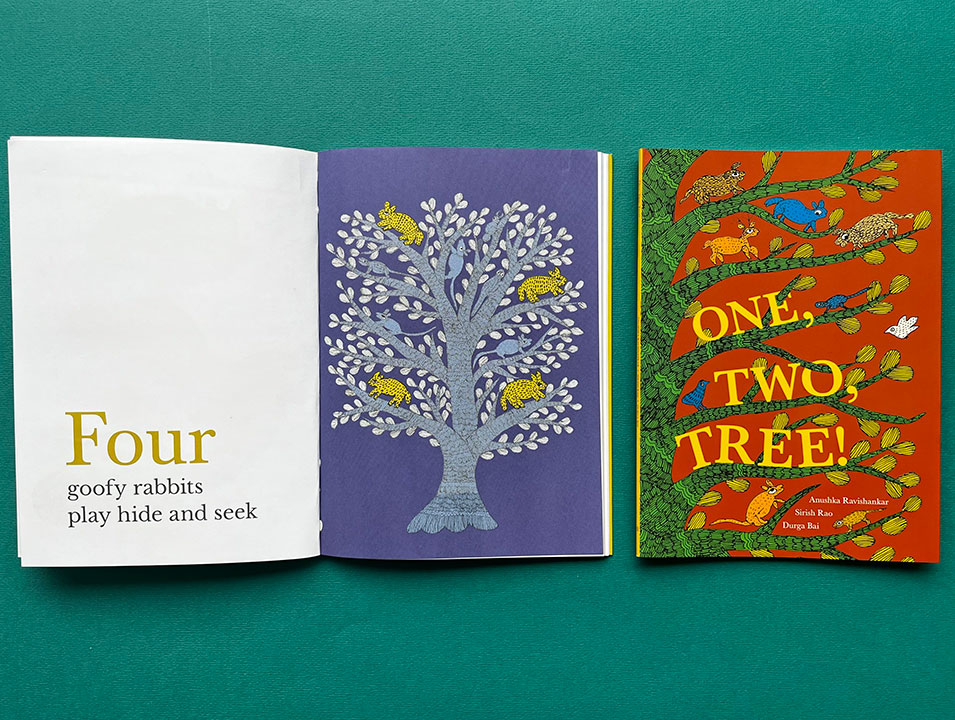

This was the case with One, Two, Tree!: Gita Wolf was taken with Pardhan Gond artist Durgabai’s beautiful trees, each of which was a world unto itself. Wanting to work with her, she came up with the idea that perhaps we could have several animals getting on to a tree that expands to accommodate them all, and have Durga illustrate it. I rendered the tale in verse, and Rathna Ramanathan designed the book, bringing in spot colours, and using the page as a sort of canvas for the text.

Many of the books I have written for Tara followed the precedent set with Tiger on a Tree — the illustrations came first, and I wrote the text afterwards. I’m often asked if this is hard to do. Actually it is much harder to face a blank page! And if the illustrations are rich and evocative, the story is hidden in the colours and the details and finding it is like an exciting game. Since I never know where the pictures will take me, the process is not at all as predictable as it may sound.

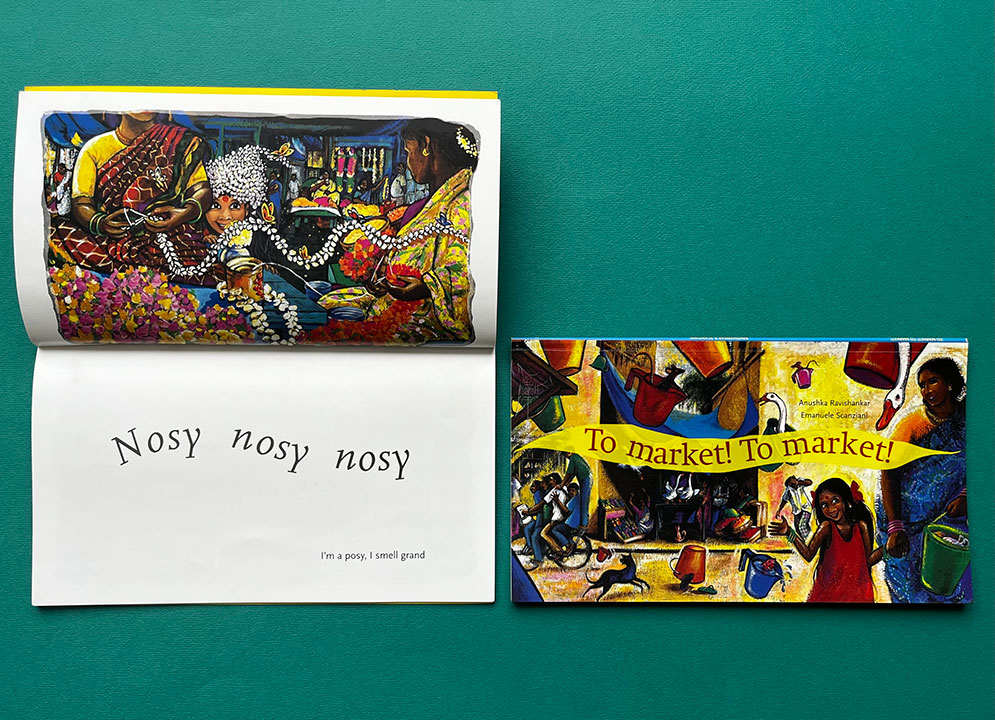

For instance, In To Market! To Market!, Emmanuele Scanziani had done a set of pictures of a market in Pondicherry, in vivid detail and deep, dramatic colours. It became the story of a girl going through a market and having so much fun that she forgets to buy anything. But before the story came the words, bounding, buoyant… and suggested by the pictures. And the story followed that joy. The verse was a reaction to the market itself (or not the market, if we’re being Magritte-ish).

There is a different kind of delight in giving the text to an illustrator and finding it transformed into something I would never have been able to imagine. One book that really left me gobsmacked was Anything But a Grabooberry. The poem started out as something I wrote with my daughter — a freewheeling poem about all the random things she wanted to be. Rathna was looking for a text to illustrate typographically and the abundance of ‘things’ in the poem seemed to lend itself well to that. The Grabooberry was thrown in as a nonsensical element. The book that came out was an amazing typographically illustrated version of the poem. It is now getting a new life with a new name I Want to Be (without the Grabooberry, and therefore closer to the original poem). The typographic illustrations have been updated and refined. And I’m still gobsmacked.

Anything But a Grabooberry and I Want to Be

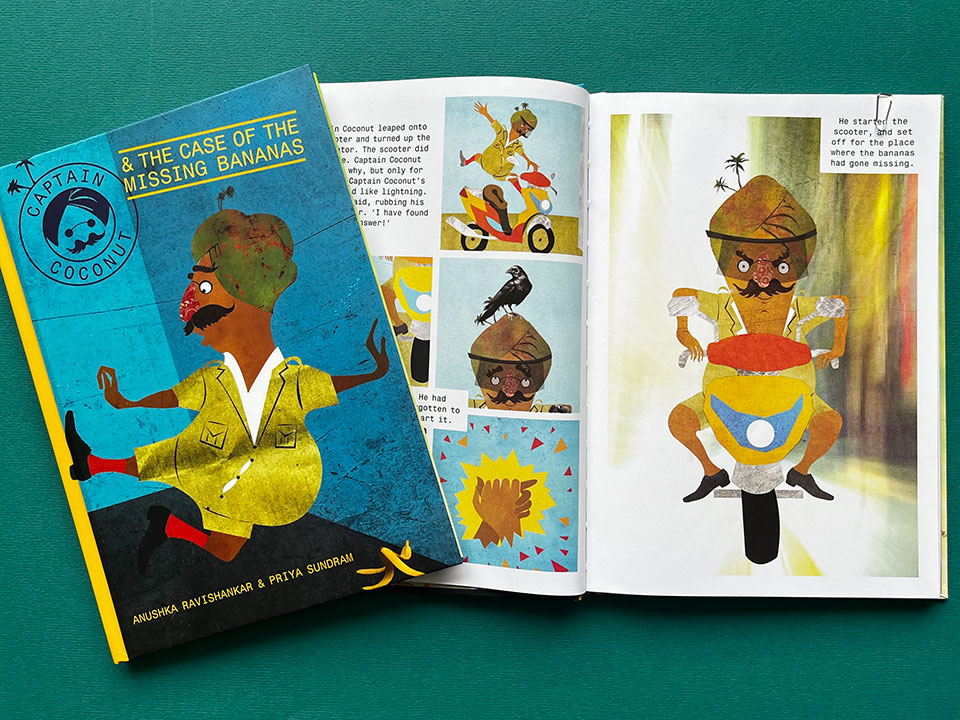

Being surprised by art is one thing, but sometimes, a story is transformed in even more astonishing ways. Many years ago, we did a book on puppets. There was a puppet character in the book, whom we called Colonel Coconut. We spent a lot of time making up a personality for this character and imagining the kind of shenanigans he would get up to, but we moved on and forgot about him for a while. But he came back many years later. He became Captain Coconut, a bumbling detective. I wrote it in a style vaguely reminiscent of the hard-boiled detective fiction of the likes of Dashiell Hammett. I felt that would be funny because Captain Coconut was such a contrast to the street-smart, canny detective of the genre. When I wrote the wacky mystery, I didn’t really think of what form it might take, so the graphic novel form in which it was published came as a wonderful surprise! The graphic elements in the book added a dimension to the story that I would not have been able to picture. There’s another Captain Coconut mystery coming out soon, and it promises to be very different, visually. I’m looking forward to being surprised yet again!

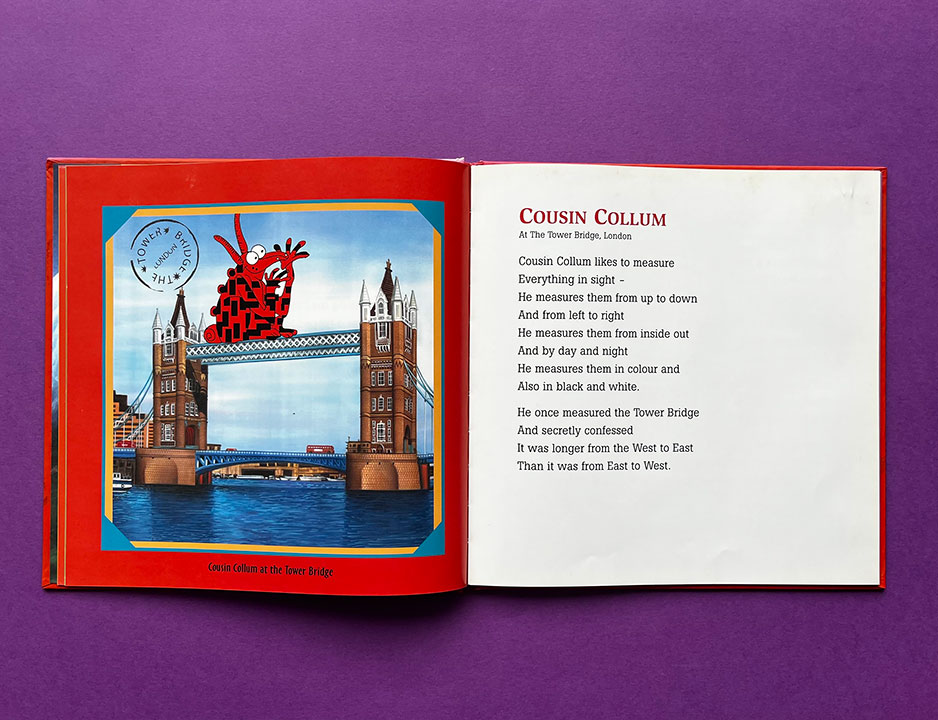

There’s a story behind every book I did at Tara — whether the illustrations came first or the words. Sometimes a book would undergo a long and convoluted process of evolution, so that the creature that finally came out in print bore very little resemblance to the one that was initially conceived. One such book was Wish You Were Here. This is one of the most purely nonsensical books I’ve done for Tara. The story was inspired by a set of weird characters created by Chennai-based artist, Trotsky Marudu at a workshop. They seemed to belong in a book of their own. We decided that they ought to be a family of travelling relatives — aunts, uncles and cousins — who send postcards of places they had seen, to their stay-at-home aunt. I had no choice but to write a series of travel tales, in verse for this book, and each of them has to do with what we know as ‘Wonders of the World’.

Wish You Were Here

Rathna added her own visual elements to the book — each ‘Wonder’ became a postcard, and we had street artists, who create those hyper-real, slightly garish posters sold on sidewalks, create these postcards. In the end, we had a rather bizarre book, featuring what I am tempted to call an alternate kind of reality. Who would have thought! Wish You Were Here is one of my favourite books, and it is clear that much of its charm had to do with the collaborative creative process.

The nonsense that I write acquires a life of its own on the page — when text and art are brought together. And it is in the creative and playful relationship between the two that sense and nonsense get paired. And here too there are several possibilities: If the words are nonsensical, and the illustrations faithful to their illogical meaning, the overall effect is sheer and happy nonsense — as it is with Alphabets are Amazing Animals as well as Hic!

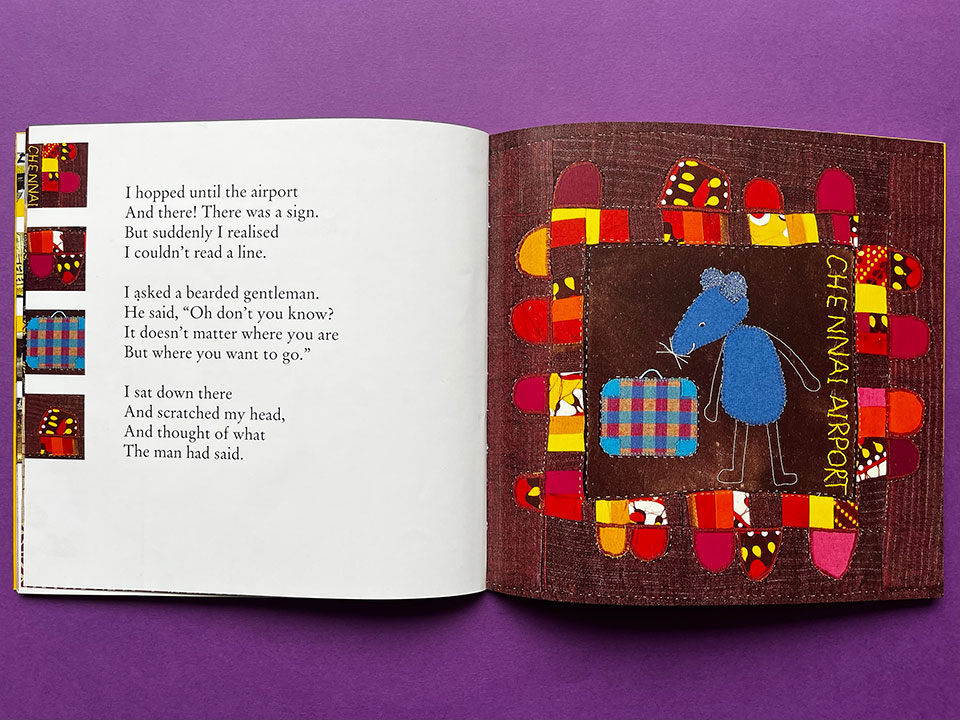

The other way around is fun as well: beautiful sedate pictures when complemented with humorous verse, can be ironic, teasing… as happened with Excuse Me, Is this India?. For this book, I wrote absurd, dream-like verse to the quilted impressions of Chennai city created by Anita Leutwiler.

Excuse Me, Is This India?

After twenty six years, and almost as many books, I am still affected by the nonsensical, the silly and the absurd. I look forward to what artists and designers make of what I write. And I am never disappointed.

Serious work: Anushka’s books

Dubbed ‘India’s Dr. Seuss’, Anushka Ravishankar is one of India’s most celebrated children’s authors, and her witty and jubilant tales are internationally acclaimed and widely translated. Anushka has now written over twenty books and travelled widely performing from her stories. In 2012, she founded the Indian children’s publishing house Duckbill together with Sayoni Basu. Click here to discover her other Tara Books. Click here to discover Tara Books she has authored.

No Comments