15 Mar To Seed

By Gita Wolf

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact moment when an idea takes hold, and I was thinking about how this book began. To go back a bit: a couple of years ago, I moved to a rural area near Pondicherry and started an organic farm. I was fascinated by plants as a child, but had to wait more than 50 years for the chance to try my hand at something like this. My favourite subject in school was botany; environmental science or natural history didn’t exist as subjects back then. It was all rather abstract, and I didn’t have much experience in actually growing anything, apart from the bean seeds I sprouted on damp cotton wool from time to time. So when it came to actually cultivating a farm, the experience was nothing like the idyll I imagined as a child—it was certainly enjoyable, but mostly hard work, with uncertain outcomes. And yet, in all this, there was one aspect which still connected me to my childhood self: the gleeful satisfaction I felt in sowing a seed and watching it sprout. All gardeners—young, old, new or experienced—know this feeling, and I began to wonder where that came from. Surely we know that is what seeds do: given the right conditions, they unfurl into miniature plants. And yet…it is miraculous, every single time.

Dispatches from the farm

As I was thinking along these lines, a local farmer friend brought me some spinach seeds from his garden. He said they were well suited to our climate and soil, and hoped they would do as well for me as they had for him. It was a perfectly ordinary thing to say, and yet—maybe because I was musing on seeds—the phrase stayed with me long after he left. We hope, and seeds carry that hope. If all goes well, there is a promise of plenty in the future.

Miracle, hope, potential… the ‘seedness’ of the seed, as a fact of existence, is amazing. The publisher in me sensed a book in there.

In a practical sense, a book on seeds was a tall ask. There is so much to be said, and so many angles from which to view it. From a philosophical point of view, a seed is neither alive nor dead. It is just biding its time for the right conditions to quicken into life. Meanwhile, it needs to survive periods of stress. Then there is the biological need to disperse and spread life. Then again, the human relationship to seeds—the farming that started me musing on all this—has a long cultural history. It really was a vast theme—with scores of books to prove it.

I’m not sure why, but I still felt curiously confident about taking it on, and my editorial partner V. Geetha was equally keen. We thought the best approach would be to bring together all the ways of viewing a seed that occurred to us. We wanted art and imagination to be part of it, along with science and history; each draws attention to different things, and leads to insights we wouldn’t otherwise have.

The next step was to look for the right artists. The first names that came to mind were Tushar and Mayur Vayeda, brilliant artists from the Warli tribe in western India. As farmers themselves, they had a keen interest in ecology and a lived kinship with nature, all part of Warli life. We had made several books with them already, including The Deep, their stunning tribute to the ocean. It turned out that the theme of seeds had a special resonance for them, and they were more than happy to be on board.

Layers of The Deep

Meanwhile, to come up with a narrative, we began to put down all our associations with seeds, in no particular order: as language, metaphor, biology, human history… it was amazing what multitudes a tiny seed could contain. Then sifting through it all, we decided that our focus would be on the generative aspect of seeds, both in situ, of themselves, as well as in the broad sense of ‘seeding’ rich connections for the reader to take forward. We settled on four themes: the seed as metaphor, the journeys that seeds make, human relationships to seeds and the powerful cultural symbol of the Tree of Life. The text was to be brief, but founded. My own lived experience gave me some confidence, but I still did extensive research on each section to make sure all the facts were correct.

Since each of these themes was unique and in a sense self-contained, we thought of bringing them out as four separate booklets, packaged together in a box. Maybe they could be developed even more—given our interest in different forms of the book, we could try to come up with special forms that embodied the content of each section. This is what finally emerged, after much experimentation on the part of our designer, Ragini Siruguri:

Seed Nature—a metaphor for life—was a pop-up, opening up magically like a seed sprouting. It turned into a basket used by the Warli people to gather seeds.

Seed Travels—the journey of seeds—was based on biology. It opened out into a long accordion form, reconstructing the lengthy journey of seeds along different landscapes.

Seed Women—the human relationship to seeds—was a glimpse into cultural history in the form of a classical book a, with a focus on the beliefs of the Warli people.

Seed Universe–The Tree of Life as a symbol–was a fold out, which mimicked the gradual transformation of a small seed into a grand multitudinous tree.

As we were finalizing the book forms, the Vayeda brothers arrived to stay at the farm. We spent a few happy weeks together, tossing around ideas. What we were looking for was not illustrations for the text so much as a parallel visual language, with its own meanings. With an intuitive grasp of what was needed, Tushar and Mayur were the ideal partners for what we had in mind. Their artistic mastery was a given, but their rootedness in Warli life—with a lived understanding of nature—brought something truly special to the project.

Tushar and Mayur at work

We had wanted to draw attention to how contemporary life—and industrialised farming—alienates human beings from the natural world. What Tushar and Mayur told us, particularly in the section on the human relationship to seeds, was fascinating. Of course, it’s not possible to turn the clock back, but there is a lot of wisdom to be received from indigenous societies like the Warlis, whose relationship to nature is truly profound. Women play an important role in this. For instance, in Warli mythology, there are three significant goddesses: Dhartari is the goddess of fertile soil; Kansari is the goddess of all living things, who carries the seeds of life; and Gautari is the spirit of connection between all things. These three goddesses are worshipped together, particularly by women. In everyday life, it is Warli women who collect, store and sow seeds. This tied in with what we knew already—historically, across civilisations, it was the women of the community who worked with seeds. They were the earliest seed collectors and preservers, making storage baskets to create what is called the ‘container revolution.’ That it continues to this day in Warli life was astonishing, to say the least.

A closer look: Details from Seed

The imagery that the Vayeda brothers finally came up with was superlative: the exquisite rendering of details could only come from deep ecological knowledge. Their art shows, rather than tells: the beauty of nature is inherent, rather than something that needs to be pointed out. We couldn’t have hoped to connect art and science in a better way.

The various elements of the project were now in place, but actually bringing it all together as a successful book took us over a year, much longer than we anticipated. The initial idea of having four paper forms in a box was sadly not working—people found each of the sections beautiful, but couldn’t interact with the content in the way we’d hoped. They missed reading some of the text, or were confused about how or in what sequence to open the book forms. We wanted to make a book, not a set of art objects, and a book has to work in the way it is intended. The reader would enjoy the way the forms embodied the content, but also be able to make sense of the narrative as a whole.

Initial experiments: Four paper forms in a box

So it was back to starting over again for us, to find a way of connecting the themes to each other. The only practical way to do this—while retaining the original idea—was to make a ‘frame’ book, hardbound and with sequential pages, and glue each theme into it, in the order we visualised. The text for all the themes would be treated similarly, appearing on the left side of the spread, while the paper form opened out from the right side page. Producing this would no doubt be a nightmare, even by our standards: making one copy was possible, but a couple of thousand? However, our confidence in our production manager C. Arumugam was unshakeable.

Trial and error

Then another problem cropped up. We had planned on using different coloured handmade papers for each section, to be screen printed and hand glued—but when we calculated the cost for the material and the labour, the price of the book became prohibitive. We’ve always tried to balance the costs of production with keeping the price as affordable as possible. Underpaying the labour involved was out of the question, so that only left us with reconsidering the material. We finally settled on a compromise: using only two colours of paper, a cream handmade paper for the frame texts, with brown kraft paper for the forms. It worked, especially since the kraft paper evoked the mud walls on which Warli art is traditionally rendered. With a dark brown handmade cover, the book was to be put into a kraft cardboard case. Now we were really good to go, and it was over to the production team.

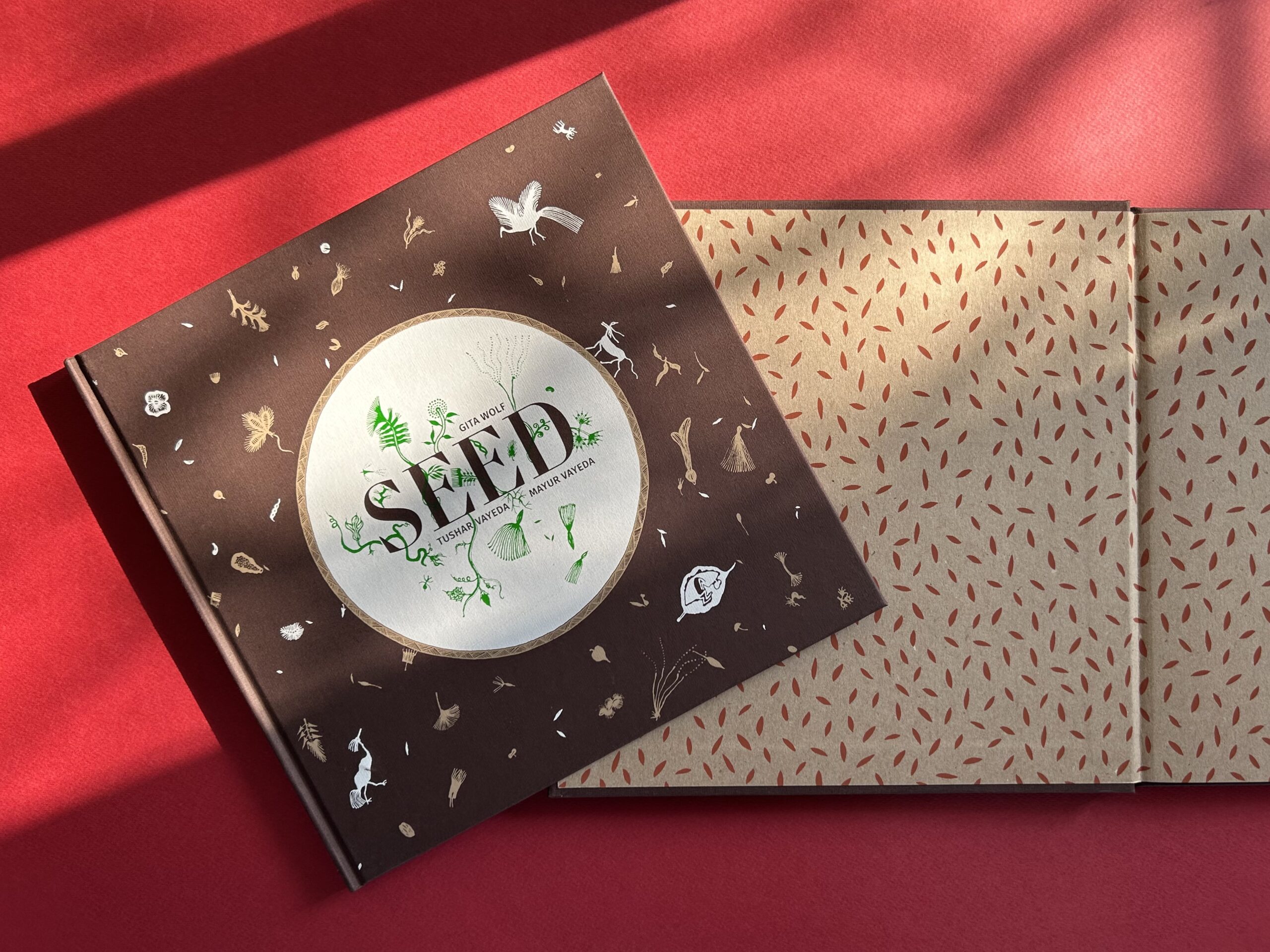

To fruition: The final cover and slipcase

It must have been incredibly difficult for our skilled artisans to put it all together—but here the book is, at last, and holding it in my hand now, I marvel at the degree of skill and precision required to produce it. It’s come a long way, growing from the seed of an idea… into the fruit of our combined labour. I confess that I was tempted by several seed metaphors while I was writing this blog—but I resisted valiantly. I hope I may permit myself this one.

Gita Wolf started Tara Books, as an independent publishing house based in India. An original and creative voice in contemporary Indian publishing, Gita Wolf is known for her interest in exploring and experimenting with the form of the book and has written and over twenty books for children and adults. Several have won major international awards and been translated into multiple languages. Click here to discover Tara books she has authored.

mihirsaswadkar

Posted at 18:32h, 15 MarchBeautifully written Gita. Can’t wait to read and see the book.

Tara Books Team

Posted at 14:43h, 18 MarchThank you for the kind words, Mihir. Happy reading!

FPhunter

Posted at 17:04h, 01 AprilVery pleased to add this book to my collection and thanks for the 15% discount. Seed is almost identical in shape to The Deep and both are illustrated by the Vayeda brothers. I might be mistaken but a pattern seems to emerge where earth (Seed) and water (The Deep) have been represented. I hope your association with these artists’ continue as you explore the other elements viz. air, fire, space (the final frontier?). Wishing your press and all your collaborators the best for the future!

PS: You have a small fan following on LibraryThing under the Fine Press Forum discussing your press and a few titles!

Tara Books: https://www.librarything.com/topic/342165

Hippolytos: https://www.librarything.com/topic/323076

Seed: https://www.librarything.com/topic/359666