31 Mar What is School a Place For?

by V. Geetha

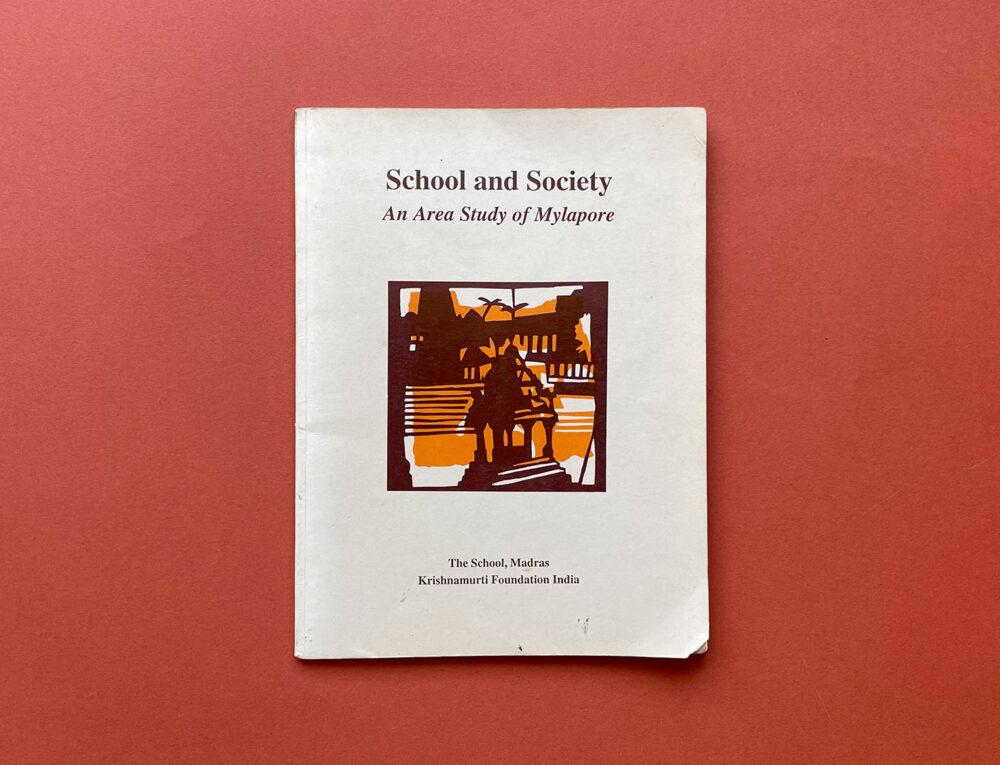

From its earliest days, Tara Books has been interested in creative pedagogy. We published School and Society: An Area Study of Mylapore in 1995, the first year of our publishing. Based on a project undertaken by middle-school students at The School KFI (Krishnamurti Foundation of India), Chennai, the book describes the enormous amount of learning that happens when the boundary between the classroom and the world outside dissolves.

School and Society (left); A spread from the book

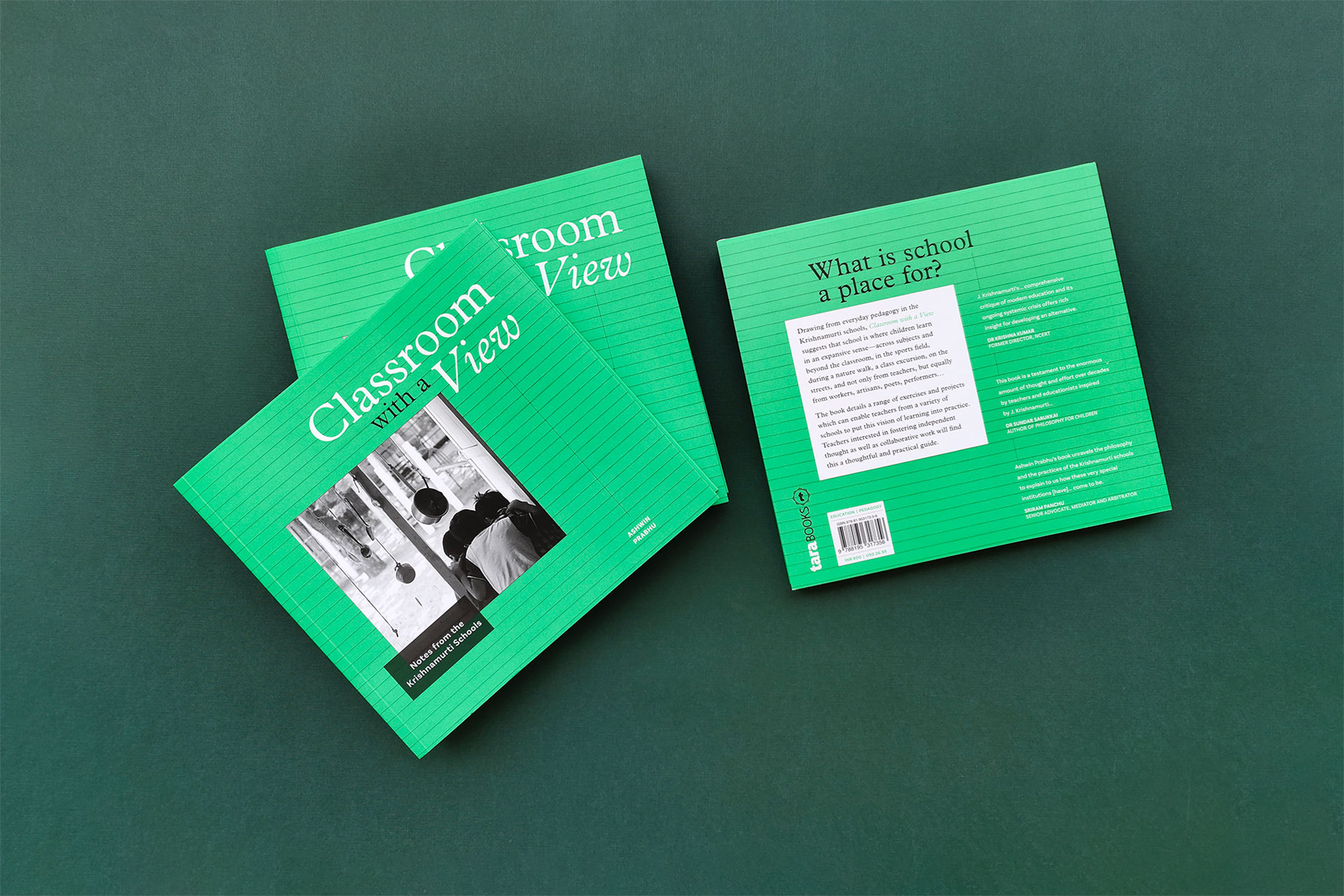

Twenty seven years later, we revisit the theme of boundary-less learning, with Ashwin Prabhu’s Classroom with a View: Notes from the Krishnamurti Schools. The book suggests that school is more than the classroom and includes the sports field, the nature walk, the class excursion… It details a range of projects and exercises to demonstrate how children learn across subjects and beyond the classroom, and not only from teachers, but equally from workers, artisans, performers, poets…

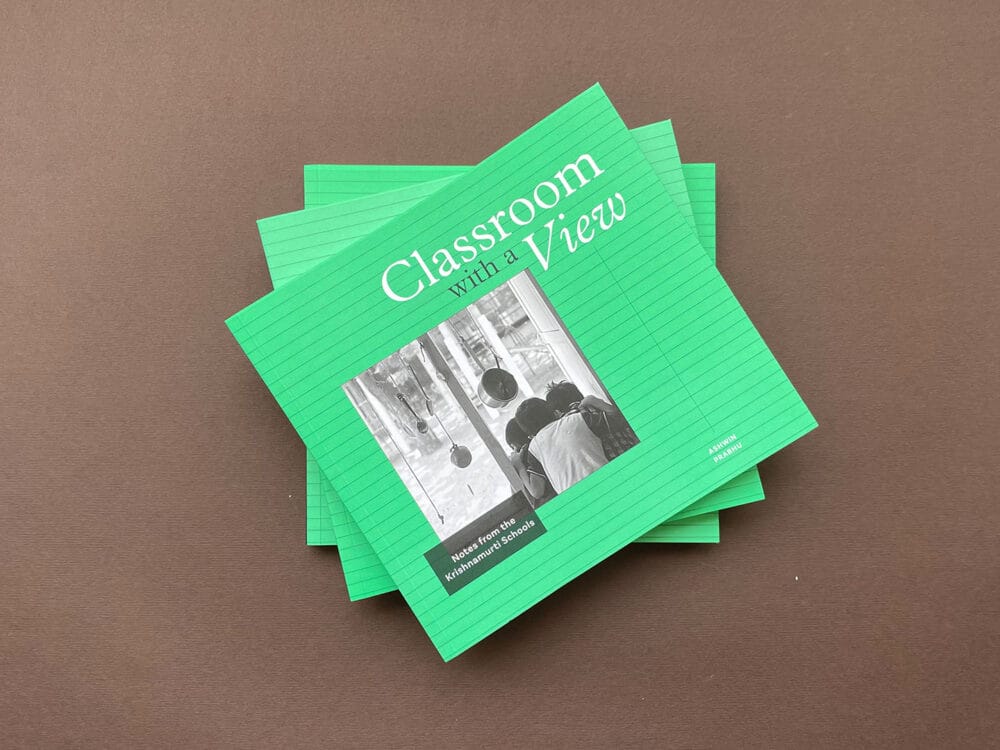

In the years that separated School and Society and Classroom with a View, Tara Books had published a number of titles with a pedagogic focus. The series Craft without Limits which goes back to 1996 comprised titles in art and craft learning, where the focus was on the process of creation, and not merely the object that was to be created.

Years later, we put out books — the 8 Ways to Draw series — that introduced indigenous Indian art traditions to children. This set of books points to the distinctive features of each tradition, and encourages children to be inspired by, and not copy or imitate, what is on the page.

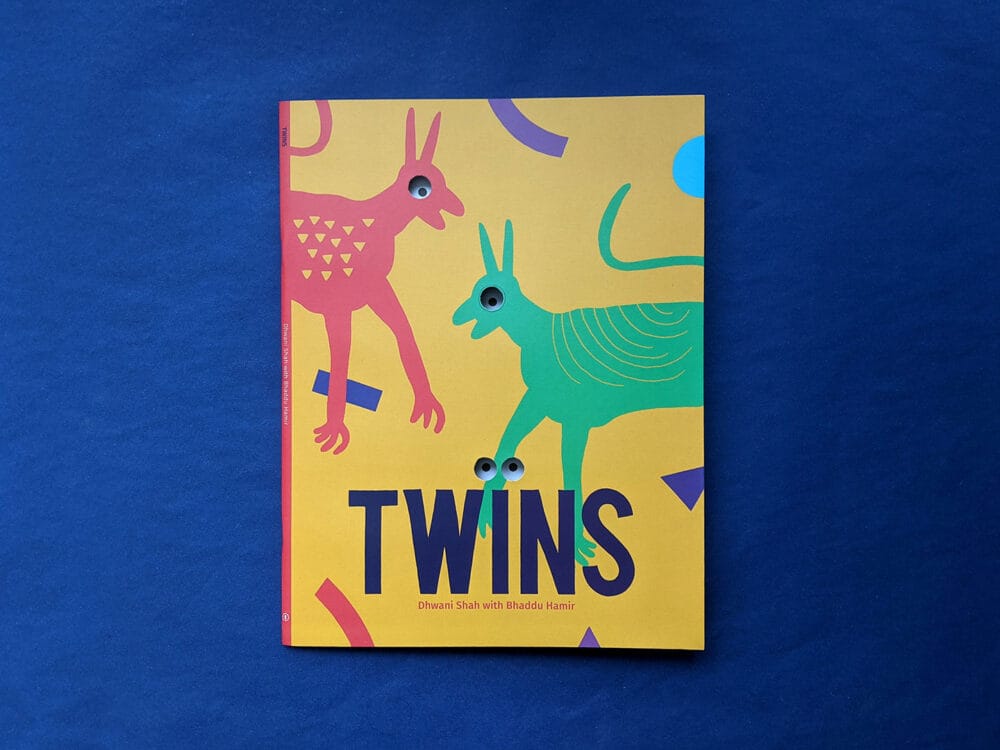

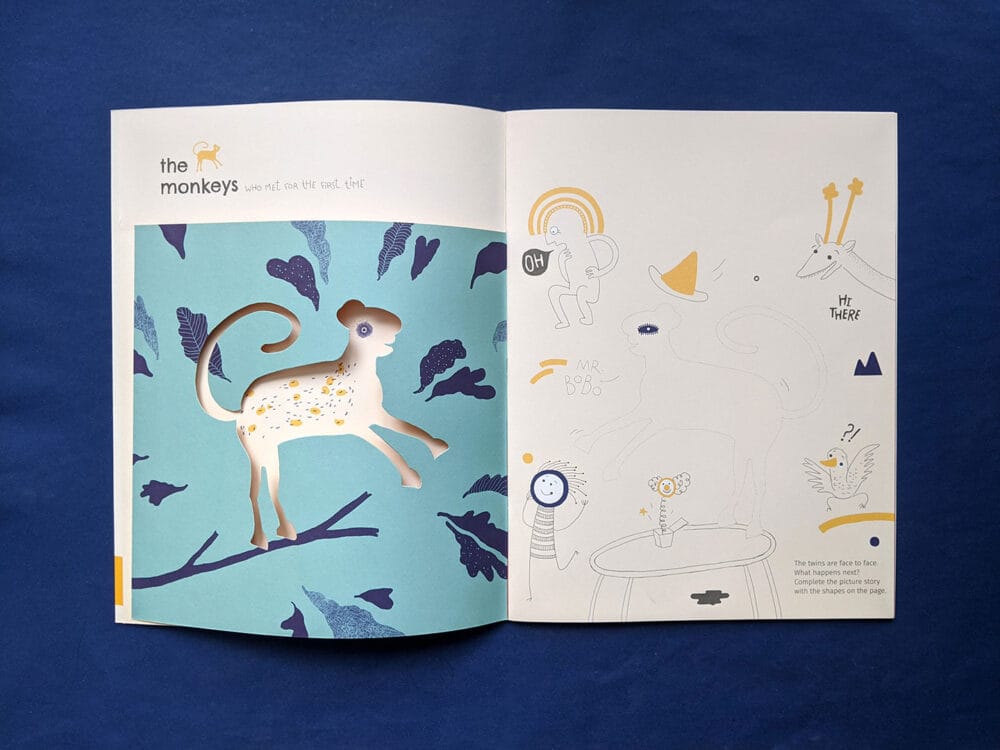

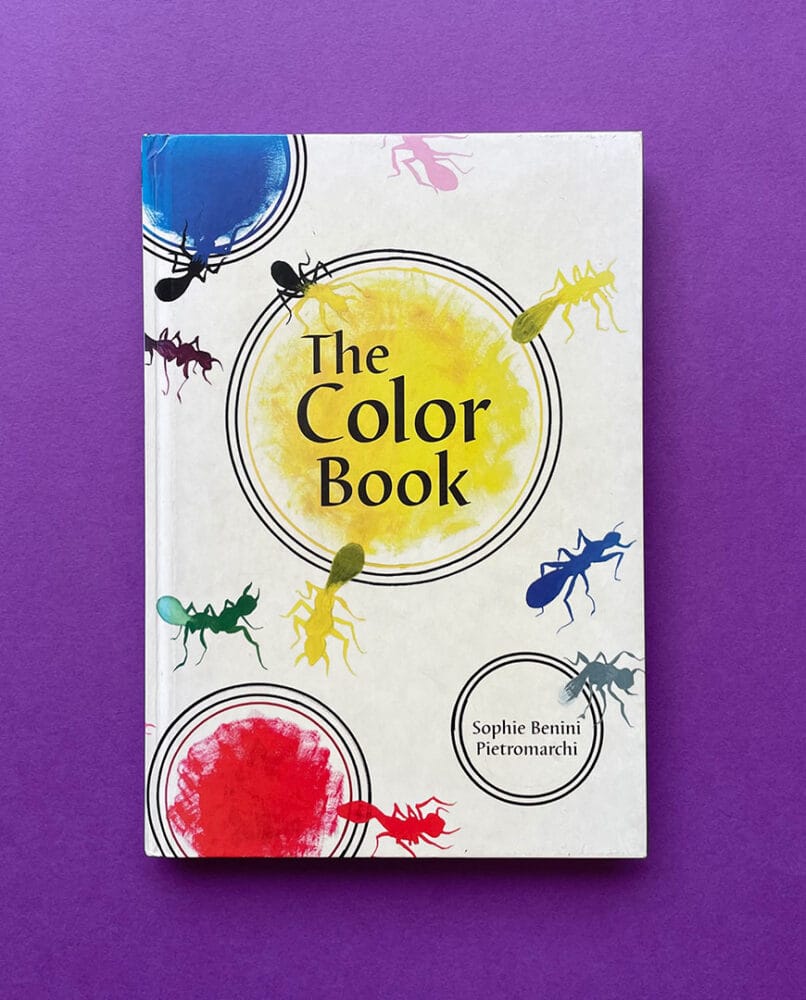

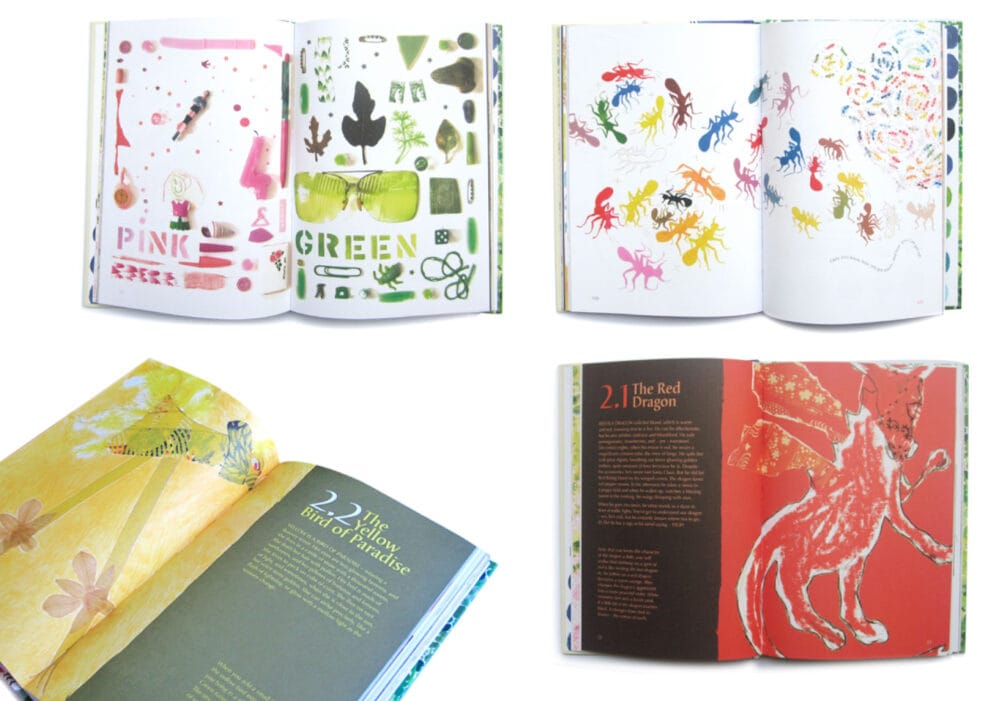

Apart from this series of books, we have published individual ‘how-to’ titles. Twins, featuring Pithora art, invites children to draw their own story based on visual clues and suggestions. The Colour Book is about the excitement of knowing and creating colour, while learning about a particular colour’s cultural meanings.

Twins

The Colour Book (left) and spreads from the book

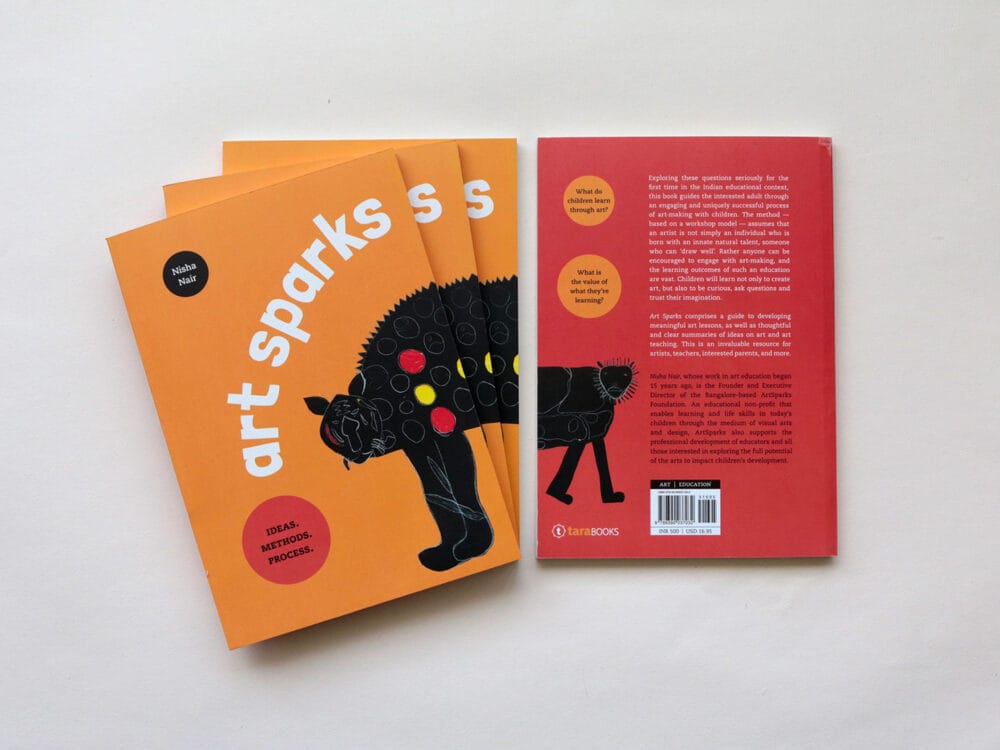

Art Sparks is both a ‘how-to’ book as well as an educator’s guide. But, it does not instruct so much as demonstrate how art might be taught. It draws from actual classroom experiences and offers a set of thoughtful reflections on art and art pedagogy.

Art Sparks: Ideas. Methods. Process.

Classroom with a View is in line with these earlier titles, but it is also more capacious in scope. Distinguishing ‘learning’ from ‘studying’, and knowledge from achievement, it makes a case for fearless, open-ended inquiry, carried out by students and teachers together. It foregrounds the child learner, as an active and dynamic co-creator of knowledge and school as a space that opens out to the world. Equally the world, both the natural and social environments that we inhabit, are seen as meaningful learning contexts. This approach to learning and education is explained and contextualised in and through references to specific everyday practices in the Krishnamurti schools.

Author Ashwin Prabhu makes it clear that the book’s content is not to be viewed as a template. Rather it is to be seen as an enabling point of departure for educators — and educational institutions — to reflect on their understanding of learning and the practices that help realise it.

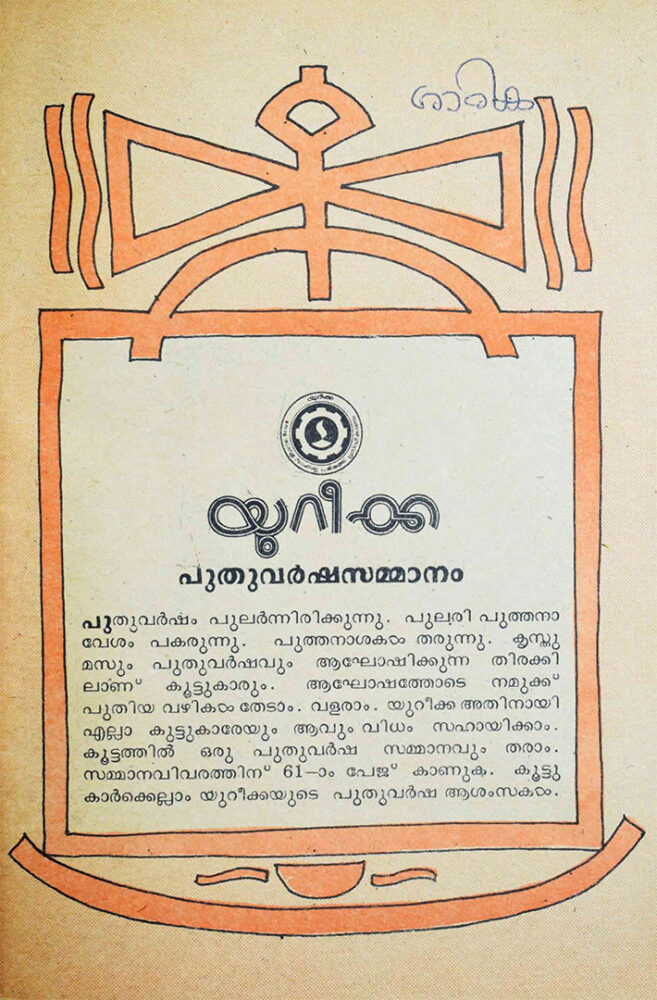

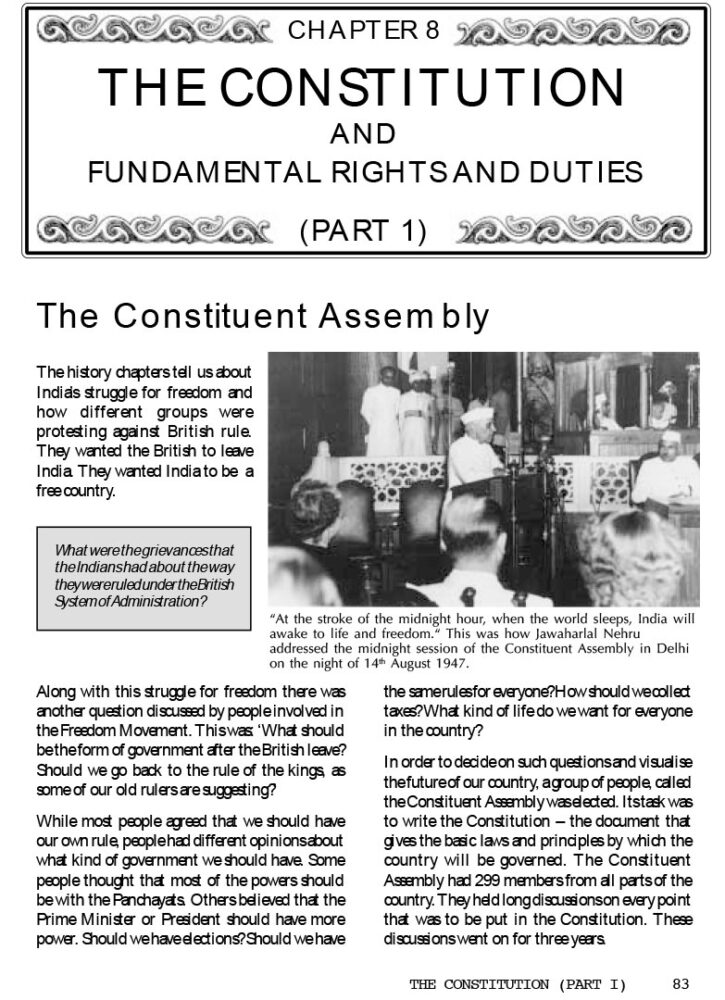

While the educational vision of the Krishnamurti schools is distinctive, it is useful to view it in the context of related educational notions and practices. Since the 1960s, vibrant debates about learning have taken place across the country, and in the context of public education and schooling. In 1968, a people’s science movement — Kerala Shastriya Sahitya Parishad (KSSP) — was launched formally in the southern Indian state of Kerala. Among other things, it sought to build what has been termed a ‘scientific temperament’, that is, a worldview that builds on the findings of modern science. As far as school education was concerned, the KSSP laid stress on learning through doing and experimentation, logical inference and reasoning. As important, it located science learning as something that has to be anchored in the child’s immediate environment.

The classroom and its immediate spatial contexts were thus linked. In turn, this linking led to the organising of science festivals in which both children and adults participated, as well as science jathas or plays and performances. The KSSP also published science magazines for children in Malayalam.

Eureka and Shastrakeralam, KSSP’s science magazines (Source)

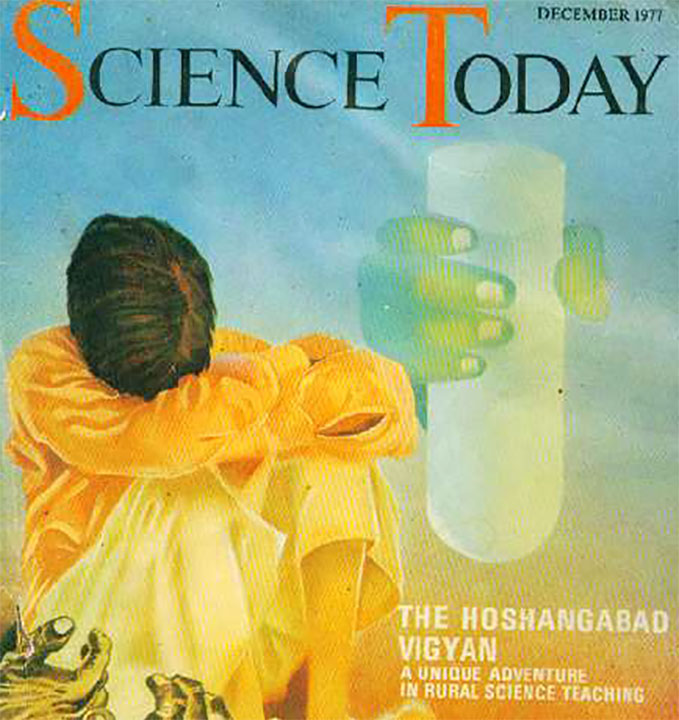

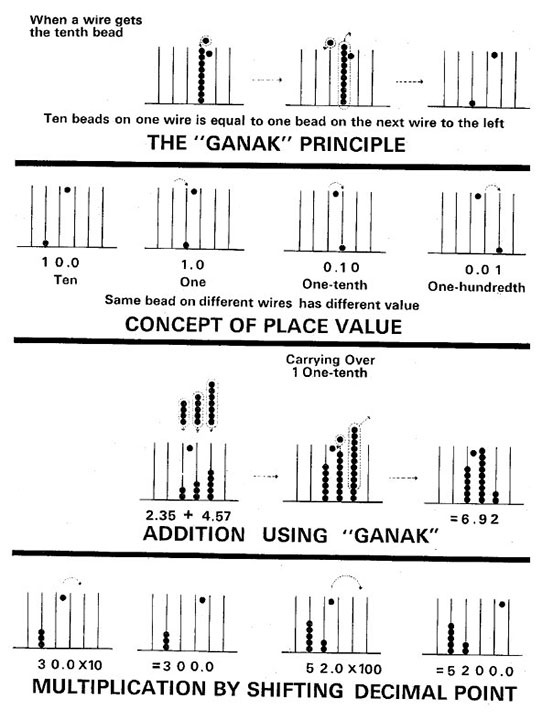

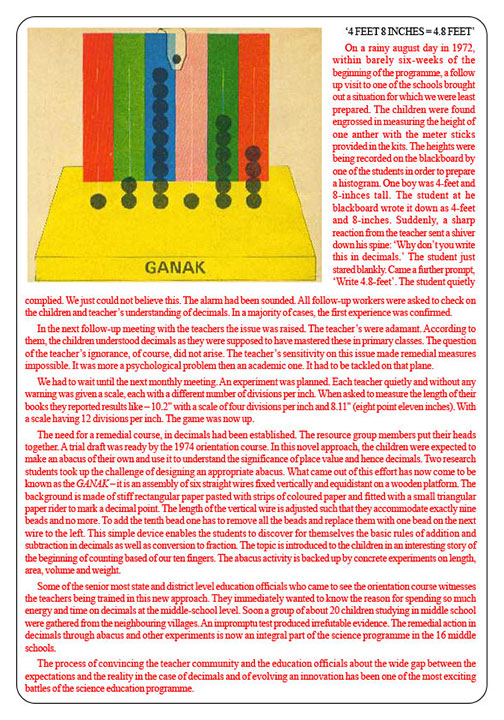

A similar effort was initiated in 1972 in central India, when a group of science teachers, social activists and scientists got together to address the state of science education in government schools in Madhya Pradesh. While the Government of India called for innovative learning strategies to be put in place in schools, teachers across the country relied on textbooks and rote learning, including for the teaching of science. To address this gap between the ideal set out in state documents, and classroom practices, this group of invested educators devised the Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme (HSTP). Science kits were prepared from locally available materials, the role played by technology in everyday life was taken note of, and teachers were trained to move away from a ‘talk and chalk’ approach to one based on experiments and ‘finding out’. In addition textbooks were reconceptualised: they drew from everyday life, and rather than exhort children to ‘know’ this or that law or principle in science, they suggested how they might tinker and experiment in the classroom to understand such laws and principles.

Science Today features HSTP (Source)

This programme was initially undertaken in 16 schools in rural Madhya Pradesh for middle-school children and teachers. Subsequently it was scaled up and before it ended in 2002, brought into its learning ambit over 1000 schools.

Even as this programme was underway, in 1982, a similar exercise was undertaken by another group of teachers and activists who gathered into a forum called Ekalavya. This time, the teachers sought to intervene in the teaching of the Social Sciences — History, Geography, Economics and Civics. Rather than teach each subject piecemeal, the Ekalavya team argued for an integrated approach, which showed the connection between these different subject areas. It also sought to centre learning on a child’s innate curiosity. Ekalavya teachers shifted attention away from memorising to learning through doing. Typically, learning began from the child’s experiences, her lived context, and from here, branched into journeys in the larger world. The Ekalavya model, along with their textbooks, became the basis for Social Science teaching from primary classes onward to class 12 in 8 government-run schools in rural Madhya Pradesh (until 2002).

Sample learning module from Ekalavya (Source)

Readers of Classroom with a View will notice that the learning practices it proposes are akin to those adopted by KSSP and HSTP and Ekalavya. Whether it is the Area Studies projects that children do in class 8, as part of their Social Science class, the experiments they undertake in what are called the design and tinker sheds, or the long excursions they undertake in class 11, when they spend time in a community, working alongside local people, and learning from them: these initiatives encourage the child to find out, innovate, ask questions and relate to, and learn from the larger environment, whether natural or social.

Classroom in the community

Tinkershed

Each of these initiatives proposes a creative model of education and learning. For KSSP, HSTP and Ekalavya, education is a public good that all children, irrespective of class and caste ought to be able to access. The state had an important role to play in realising this objective — not just in terms of ensuring equal opportunity, but also in rendering the classroom a lively, dialogic place, where children learn through discussion, doing, and from each other, as much as they do from books and lectures.

The Krishnamurti schools view education as the art of learning, not only from books and teachers, but from what J Krishnamurti defined as the ‘whole movement of life’. Yet for these educators, the physical space of the school continues to be important as well — for the meeting of generations, their mutual interaction and for cooperative as well as quiet learning.

In an era of exploding digital alternatives to the schoolroom, it is perhaps good to remember that learning is not only about ideas and information, which digital sources supply in abundance. It has also to do with spontaneity, with the unexpected and the serendipitous. In this sense, Classroom reminds us that school is a place for interconnected and experimental learning — it is centred on a shared space, but leads the learner outwards into the world, as well as inwards into community

READ A CHAPTER FROM CLASSROOM WITH A VIEW:

V. Geetha is a writer, translator, social historian, activist, and a freelance editor and a leading intellectual from Tamil Nadu, India. She has been active in the Indian women’s movement since 1988, organizing workshops and conferences. Geetha has written widely, both in Tamil and English, on gender, popular culture, caste, and politics. Click here to discover Tara Books she has authored.

No Comments