22 Feb Collaborative Nonsense

Nia Murphy & Maegan Dobson interview Anushka Ravishankar

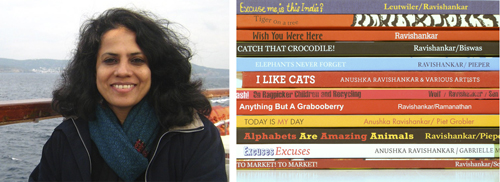

More than 20 years after the publication of her first book, India’s acclaimed nonsense poet Anushka Ravishankar looks back at the collaborative process that led to the creation of her first few picture books for children.

Tiger on a Tree was your first book. How did the project begin and evolve?

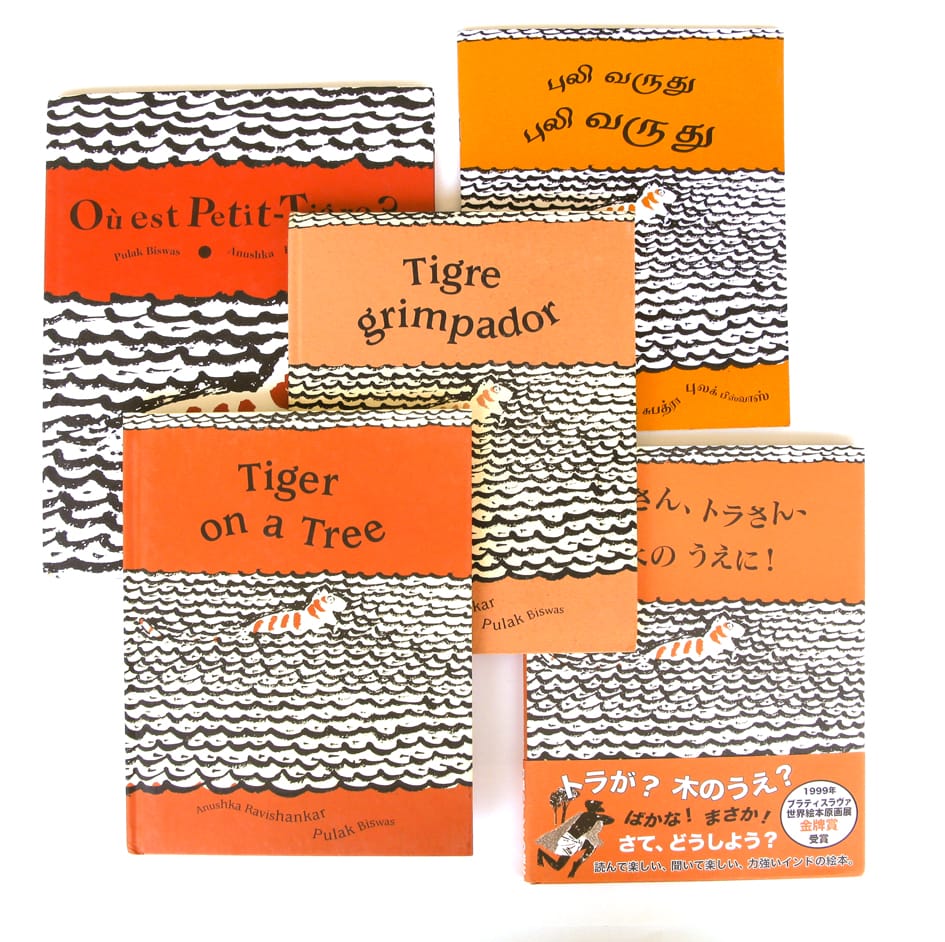

The point at which I came in was when Tara had already held an illustrators’ workshop, which Pulak Biswas had attended. At the workshop, Pulak told Gita Wolf (Tara’s founder) a partly true story about a tiger that strayed into a village, and then Gita asked him to illustrate it.

As the story was already told in pictures, the question I had to grapple with was what I could add in the text that was not already there visually. That’s when I thought – since I had always liked nonsense – that I would try writing that.

Of course, Tiger on a Tree is not completely nonsensical, but the words are slightly tangential to the pictures. So that was a nice first book to do because I had the story already. But at the same time, I had to think of ways in which the text could do more than the illustrations were already doing.

How is the process different for you as an author between writing a text that is then illustrated compared to writing a text when the pictures are already done?

It’s hugely different. What I enjoy about picture books is the tension between the text and the illustrations, and the way they play off each other. If I write the text and then give it to an illustrator, then the job of creating that tension falls to the illustrator. On the other hand, if I have the illustrations with me and then write the text, then that job is mine.

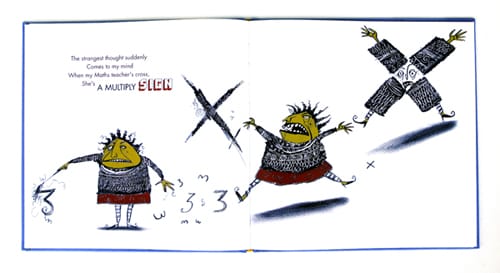

I do like it when I write something and then see what an illustrator has done with it, for example as was the case with Today is My Day (currently out of print). For this book, Rathna Ramanathan (Tara’s designer) and I came up with the idea of the child who wants to do everything her way on one day. I wrote the text and gave it to the illustrator, Piet Grobler, who did a fabulous job with it. So even though I wasn’t involved once the text was given to him, it’s one of my favourite books because it came back with a whole new dimension that I hadn’t thought of myself.

A cross math teacher turns into a multiplication sign in Today is My Day

So do you prefer one way of working over the other?

It’s actually nice both ways. The good thing about working with illustrations that are already there but which are not already telling a story, like in the case of Excuse me is this India?, is that you have to create the story yourself using the illustrations.

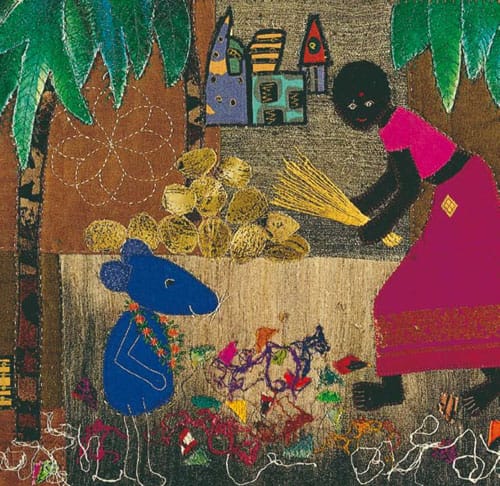

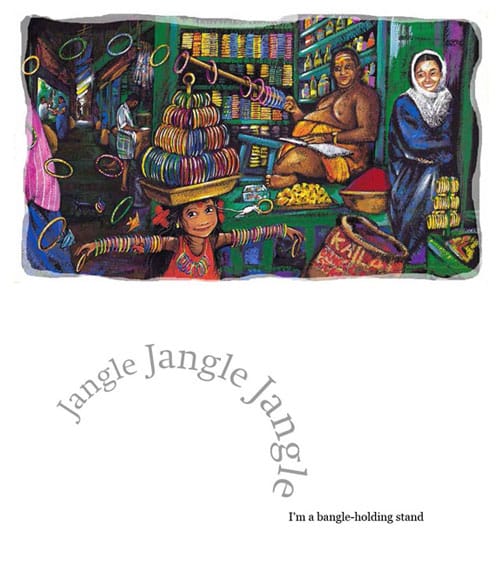

You find that when you’re looking at the illustrations there are little things that strike you, which then feed into the narrative. I’ll give you an example. In Excuse me is this India? there is a page in which there is a girl who is making the floor design, the kolam, outside her house. So the verse on that page took off from the design – it is all about a map without a place and things like that. So that’s a very fun thing to do: to look for little things and then spring off that and make up verse.

There are also other ways aside from these two ways of working with illustrators, too. After Tiger on a Tree the next book that I did with Pulak Biswas was Catch that Crocodile. In this case the whole story was given to Pulak, he then did the illustrations and then I wrote the verse.

What’s the most unusual way in which you have worked on a book?

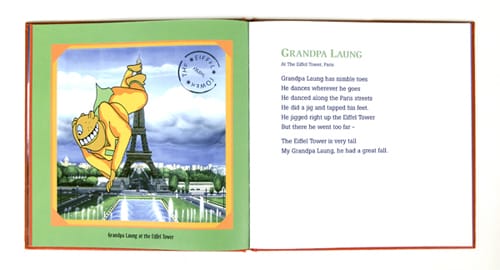

I think that Wish you Were Here is probably the most oddly evolved book that I’ve worked on. We had these little characters created by Trotsky Marudu, and we decided that we needed to use them in a book. I remember that we were just talking about it in the Tara office – Tara’s designer, me, and Gita. We kept throwing ideas around, so in the end we didn’t know who came up with the idea first and how it happened.

In the end, we decided to do a book about a family traveling, and we placed the characters in these different contexts: the Eiffel Tower, Tower Bridge in London, the Egyptian Pyramids and so on. It was such a complicated process!

Funnily, the book that came out of it is one of my favourites, Perhaps it was a little too off-centre for most people, but that again is one of the best things about working with Tara. You can do off-centre things that you can’t do with other publishers, and there is no strait-jacket.

I’ve been really lucky, because I’ve worked with so many different kinds of illustrators, styles and different ways of making a book. And that I think is the fun thing – you don’t just write in a vacuum. The nice thing about picture books is that there are so many things involved, and they all have to come together just right to work.

And then there is an extra step, isn’t there? When both the text and the illustrations are finished, the book is then handed over to a designer. How have you found that process?

That’s true. With Tiger on a Tree the designer Rathna Ramanathan brought a completely new aspect to the book. The illustrations were black and white to begin with and the touch of orange was added by her.

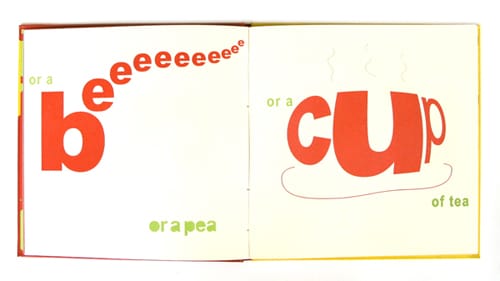

One of the very striking things about Tiger on a Tree, of course, is the typography. You have no idea the number of people who have seen the book and then said, “We’re going to try this in our books now!” It really does change the way you read the book when the text expresses the word in a different way. After Tiger on a Tree Rathna and I worked together on Anything but a Grabooberry (currently out of print) which takes this a step further and uses the text as illustration.

I like the way Rathna uses white space as well – the way she frees up the text and makes the page such a beautiful thing to look at.

Language and typography come together to create word-illustrations in Anything but a Grabooberry

Your use of rhyme and rhythm is very distinctive. Is that something conscious, and how do you think it fits in with other children’s and nonsense verse?

See, I don’t see that one starts writing with an idea of whether something is like or unlike something else. Every narrative has its own rhythm. As I said, Tiger on a Tree was my first project, and I just went with the pictures and did what they suggested.

If you read the book, there is a kind of structure to the verse, but at the same time it’s not very regular rhyme and I think you’ll find that with most of my books. I don’t like to stick to too regular a rhyme pattern because I find that it gets boring. So I deliberately break it: there are halts and then it takes on a different rhythm.

Those are things that I do because I just like doing them – I don’t know if it’s right or wrong or whether it’s like anything else or if it’s different from anything else. You just let the story decide the rhythm. If you look at To Market! To Market!, the rhyme patterns are fairly standard, but because the picture are so rich and what the words are saying is so different, then in that case that works.

Is there anything that has defined and unified the process of working with Tara, even though each individual project has been so different?

With Tara it is always collaborative. And the nice thing also is that I think there is a certain matching of wave lengths, so that when we are saying something one doesn’t have to explain oneself, the other person just takes it off from there. A certain resonance happens and that’s something that I really treasure.

Dubbed ‘India’s Dr. Seuss’, Anushka Ravishankar is one of India’s most celebrated children’s authors, and her witty and jubilant tales are internationally acclaimed and widely translated. Anushka has now written over twenty books and travelled widely performing from her stories. In 2012, she founded the Indian children’s publishing house Duckbill together with Sayoni Basu. Click here to discover her other Tara Books. Click here to discover Tara Books she has authored.

Pingback:Michael Prusse: «Tiger on a Tree» by Anushka Ravishankar, illustrated by Pulak Biswas – Children’s Literature Blog

Posted at 18:25h, 09 April[…] Ravishankar’s page at Tara Books also contains an interview in which she shares her thoughts about Tiger On a Tree […]