22 Apr Hidden Threads: Making A Stitch Out of Time

by Anaïs Beaulieu

An embroiderer’s skill is actually revealed by the quality of the work on the reverse side of the fabric — the hidden intersection of threads and knots that hold the embroidery in place. It is not seen immediately, and yet must be impeccable. Perhaps a book works somewhat like embroidery. Its pages are held together by a thread that is also hidden. It is behind the scenes but without it, nothing exists. It is the symbol of what we do not tell and which, nevertheless, is necessary.

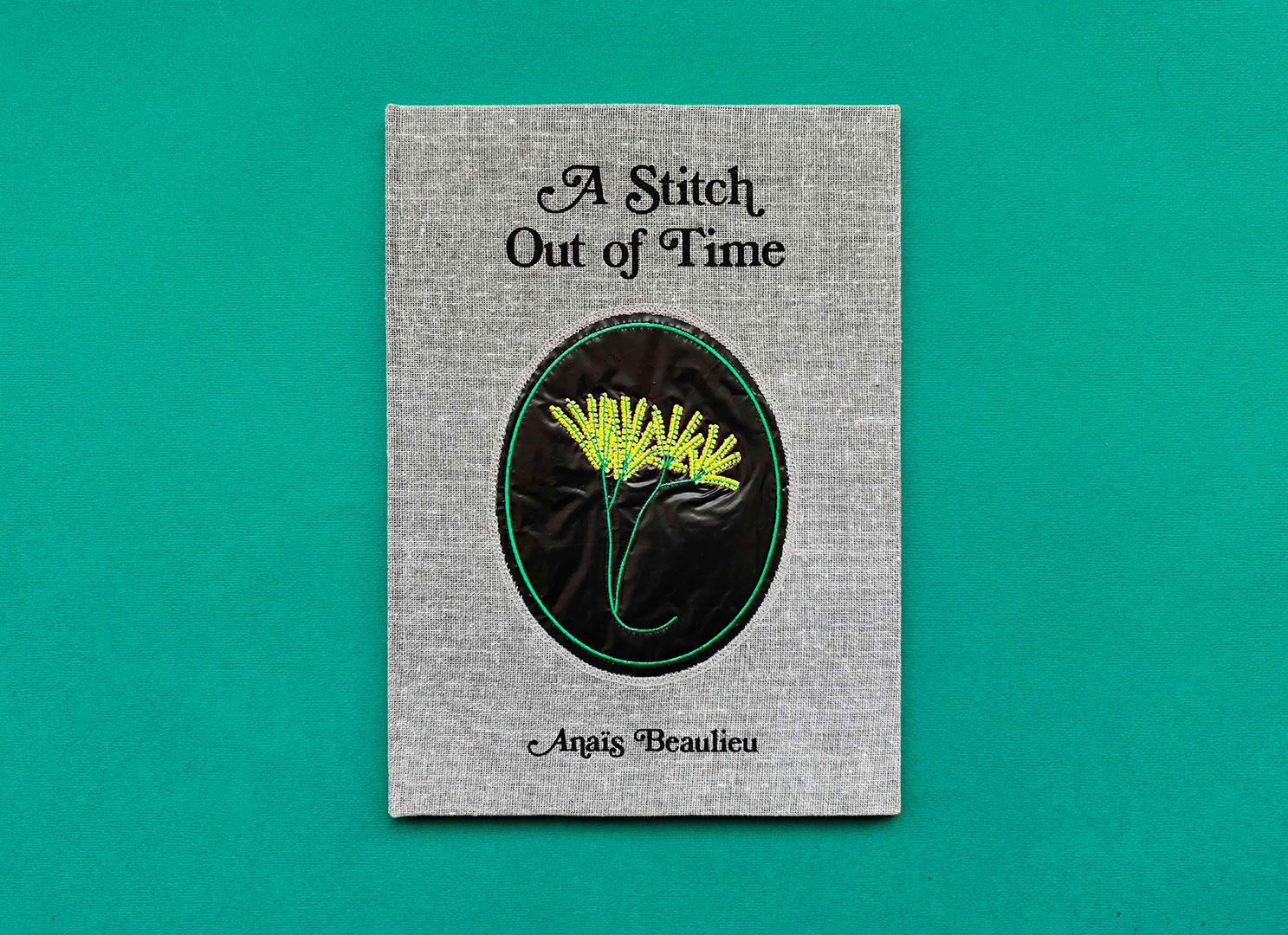

Out now: A Stitch Out of Time

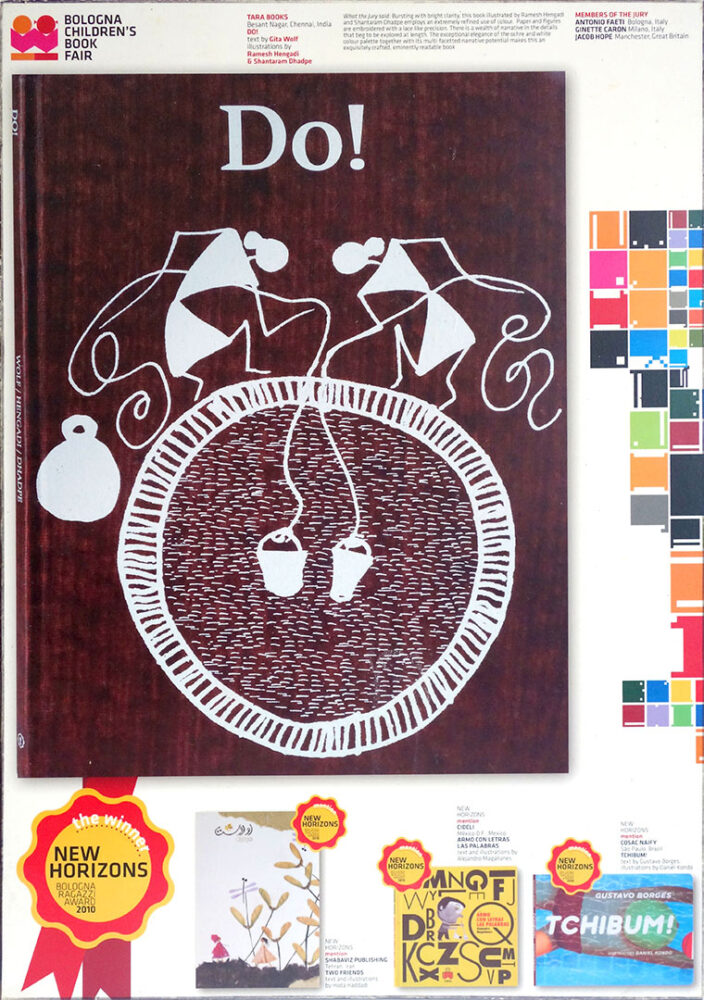

The story of A Stitch Out of Time began in 2010. After graduating from art school, I worked for a while as a bookbinder before joining Les Trois Ourses, a publishing house that makes picture books for children. This led me to the Bologna Children’s Book Fair where I met the publisher Gita Wolf of Tara Books. Their title Do! had won the Bologna Ragazzi award that year. My experience as a book binder made me appreciate the artisanal skills that had gone into the making of their books, especially the handmade ones. Tara was proving that it was possible to actually craft books.

New Horizons award for Do!

In 2018, I returned to the book fair at Bologna but this time as an exhibiting artist. I had just completed a book that showcased a series of embroidered handkerchiefs. I met Gita once again and had the chance to present my work. We were both interested in continuing a conversation we had started, on traditional skills and workmanship, and also to explore our shared values. The director of the Alliance Française in India at the time, Pierre-Emmanuel Jacob, and the French Institute in India made this possible and I set off for India later that same year on what was to prove a wonderful adventure. I take this opportunity to thank them warmly.

Threading ivy on plastic

I arrived in Chennai with a project I had been working on — a plastic bag on which I was embroidering an ivy plant. The idea had come to me in Burkina Faso a year earlier, when I had driven by a field choked with plastic bags. When I showed Gita this work, she said, “Let’s do a book, featuring your embroidered plastic.”

While I had a few other pieces of plastic, embroidered with plants, these were not enough for a whole book, and I decided to do more. After a conversation with Gita and editorial director V. Geetha, we decided that the embroideries I was yet to do would highlight Indian plant species that were potentially threatened. I began researching the topic, but the question proved to be quite complex. Sometimes, a species was threatened in one region and not in another — this was the case of the Gloriosa superba. Others were specific to a single region such as Amentotaxus assamica, which is endemic to Assam in north eastern India. But there was one plant in particular that caught my attention, Psilotum nudum. It was threatened not only in India, but worldwide and was a critically endangered species according to the IUCN Red List. This is the plant that now appears on the cover of the book. I worked on some of the pieces while I was in India and completed the rest in France. Meanwhile, I was also asked to write a set of short texts that would accompany the embroideries.

The Psilotum nudum: stages of the process

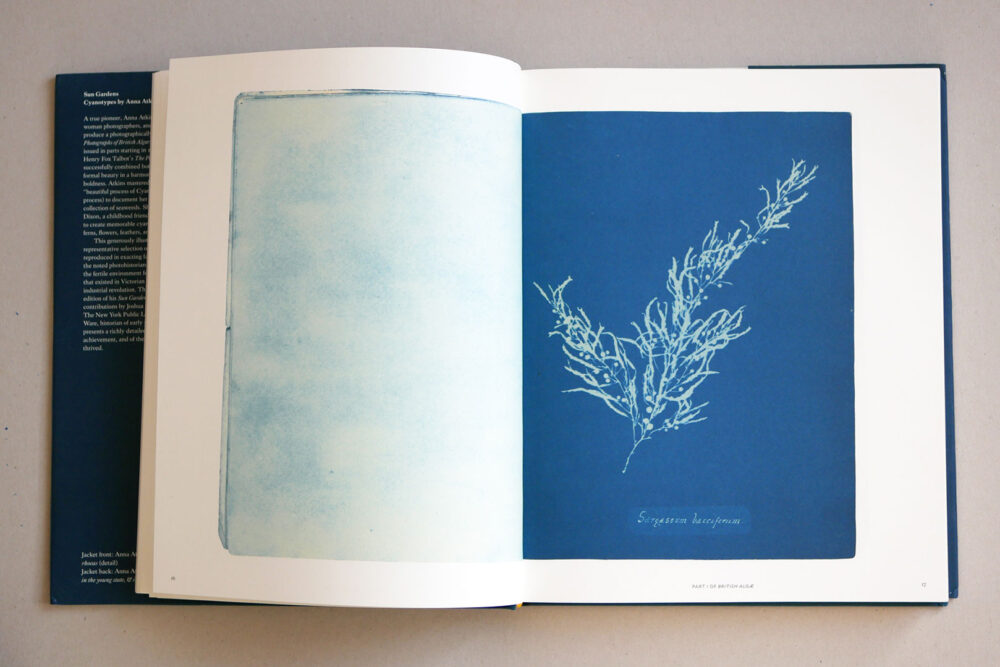

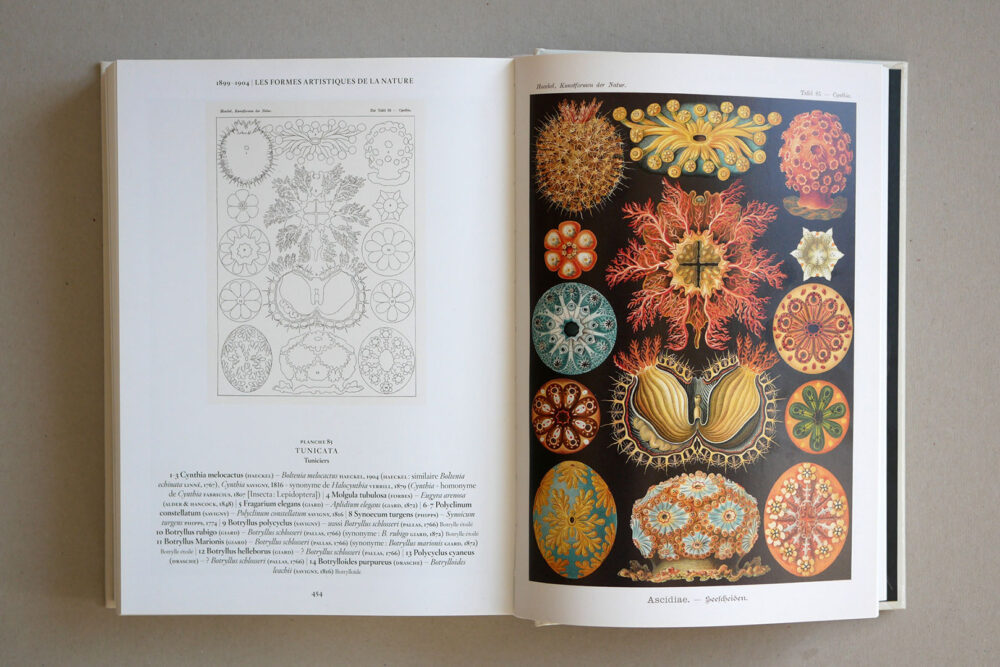

My early embroideries for the project were inspired by the herbaria of Anna Atkins and those of Ernst Haeckel. I would transfer the preparatory drawings I made for this project onto blue carbon paper — something that was reminiscent of Atkins’ boards. The threads that were embroidered on the black plastic backgrounds made for an interesting contrast that recalled Haeckel’s illustrations. These visual references guided our conversations on the book’s design.

Drawing inspiration from Atkins (Left) and Haeckel (Right)

Gita, the book’s designer Ragini Siruguri and I settled on a simple layout. Photographs of the embroideries would feature on the page but with the edges of the plastic bag cropped out. This way readers would not immediately recognise the bag and instead get to focus on the embroidery and the material it was placed on. When it came to the cover, Gita suggested that it feature real embroidery on plastic.

Photograph, illustration and text come together

We discussed the cover design with Arumugam, who is in charge of book production at Tara Books. He pointed to the technical constraints that needed to be addressed, if we were to realise our idea for the cover. First, the plastic that would go onto the cover needed to be backed by a thin fabric, so that it didn’t tear while being embroidered. Secondly, it might not be feasible to create the cover embroidery by hand, in fact it would be impossible to make so many copies: it would have to be done by machine.

I made an embroidery-model of the Psilotum nudum, scaled to the size of the plastic that would appear on the cover. Arumugam then presented this to a tailor as a sample. We were surprised by the first results — the tailor had created a blue Psilotum on a red plastic bag. His work was beautiful but not quite what we wanted. On the other hand, his reaction was interesting: it gave meaning to this book. Arumugam explained to the tailor why we wanted the embroidery done on plastic. And when he understood that, he gave us some feedback — he pointed out that given the constraints of the sewing machine, it might not be easy to replicate complex embroidery patterns. I simplified the design thereafter and eventually we arrived at the version that now adorns the cover.

Early experiments with the tailor

My time in India allowed me to immerse myself within Tara’s warm team and gave me the chance to observe their silkscreen-printing and bookbinding workshop first-hand. I’m very grateful to them for welcoming me. It was also an opportunity for me to observe and learn from the great traditions of textile production and embroidery in India. I have collected and stored a lot of images and samples, which I hope will prove useful for other projects in the future.

At work in Book Building, Chennai

Once I was back in France, I resumed work on the four pieces I had left to do. I also began work on the text that would accompany each page of embroidery. I decided that each plant would be captioned with its botanical name. Each would also come with a set of observations, some to do with botany, others that were symbolic and yet others that were of a historical nature. In some cases I added small anecdotes, drawn from my personal life or from associations that appeared to me during the process of embroidering. In all, it took me nine months to finish the project.

During this time, Ragini continued to work on the layout. We also needed to finalise the design for the book’s cover. While we had resolved the technical constraints of the embroidered plastic, there were other issues that had to be solved. For the title, we had initially thought I would embroider the words, and we would then scan these and use them on the cover. But when we tried this out, we saw that while beautiful, the text, unfortunately, was not readable. After many experiments, we chose a simple and screen-printable typeface.

Embroidering type trials

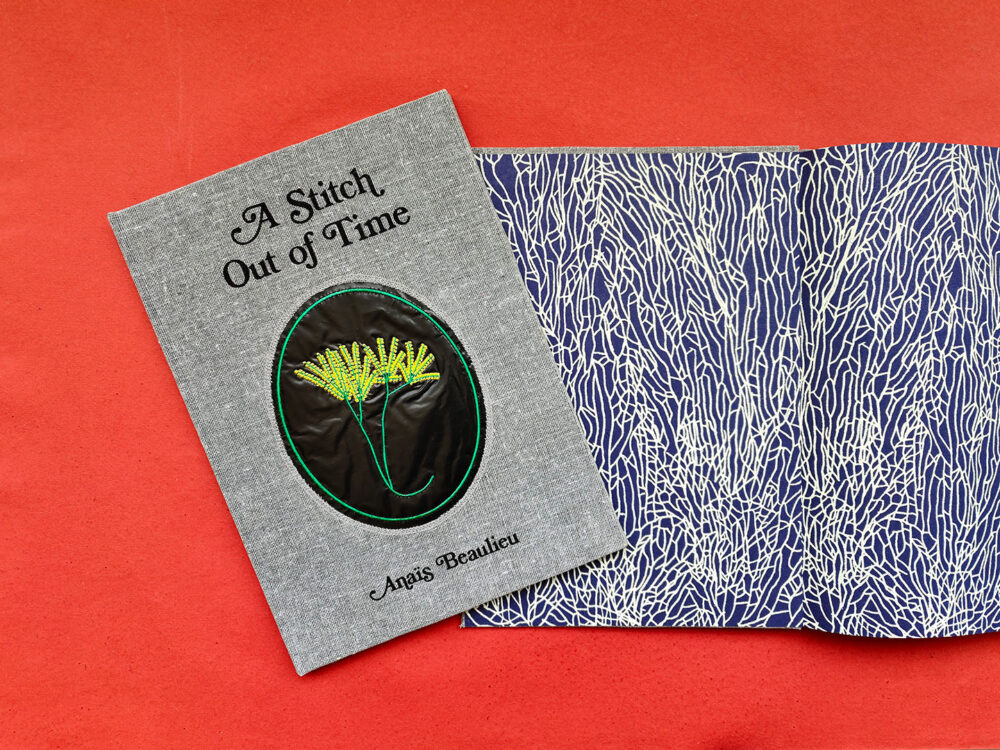

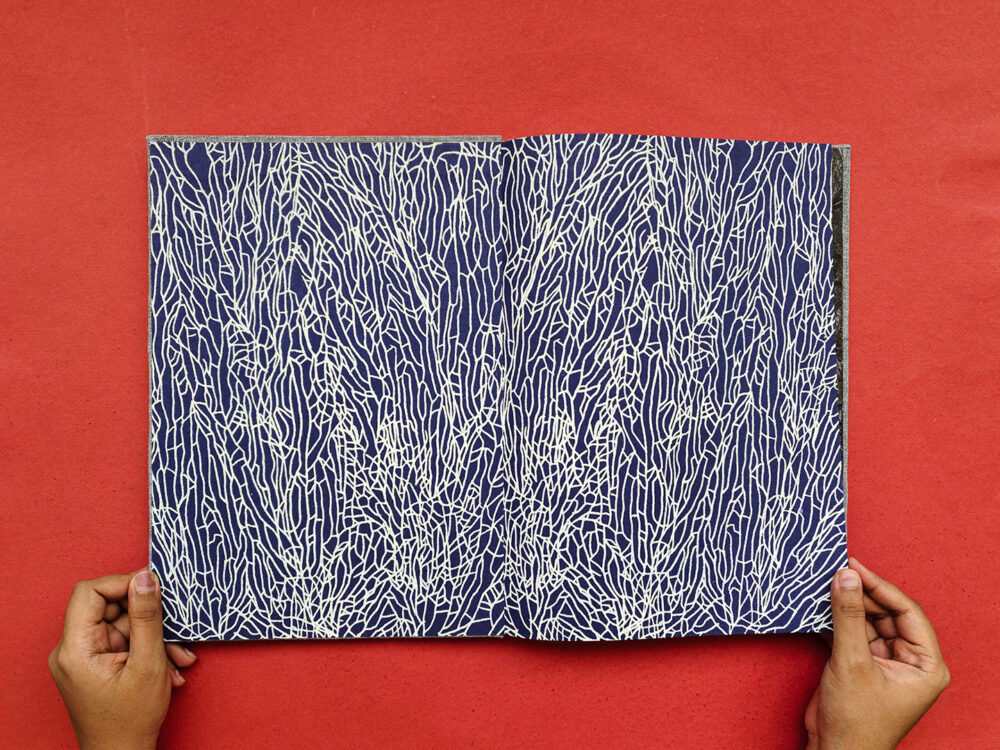

I had provided Ragini with some of my preparatory drawings, which she added to the pages as small thumbnails above the lines of text. We liked the effect and decided to use one of these drawings on the book’s endpapers. I chose the Annella mollis because it symbolises calm and serenity and reworked the illustration to fit the scale of the endsheets.

Preparing the endpapers

Given the material I had worked on, it was not possible to screen-print the entire book. Yet it seemed important to bring in an element of serigraphy, and this is when we decided to screen-print the cover and endpapers. So the inner pages of the book were printed at a conventional press while the cover and endpapers were printed and bound in Tara’s workshop.

The project in fact brought together embroidery, binding and screen-printing, all valuable manual and artisanal skills. Tara and I share a common understanding, to do with the connection between art and craft, and what it might mean to use them in our time. We also have a founded sense of the skills and know-how which is required for this kind of work. The production reflects these points of convergence and is also testimony to the commitment that we both have towards working carefully with the making process.

By end-2019, the book’s design was nearing completion. Two months later, the global Coronavirus pandemic began. However, like a seed in winter, the book was quietly dormant, but getting ready to germinate during that time — we used the time to make some modifications to the design and began to try out production possibilities. Tara had just set up a textile workshop, and we came up with the idea of a special embroidered bag for the book. We wanted the delicate cover of the book to be protected, and at the same time offer readers a chance to try their own hand at embroidery – this they can do on one side of the bag.

The embroidered tote bag

Stitch your own tote

During the lockdown, I read several books by Gilles Clément, the renowned horticultural engineer, landscape architect and writer. I was struck by his idea of a planetary garden — a means of living in harmony with nature, appreciating the ecosystem in all its diversity, and acting as gardener and custodian. I wrote to him about A Stitch Out of Time and wondered if he might want to write a blurb. Two days later, I was very happy to receive the text that appears in this book.. I thank him once again.

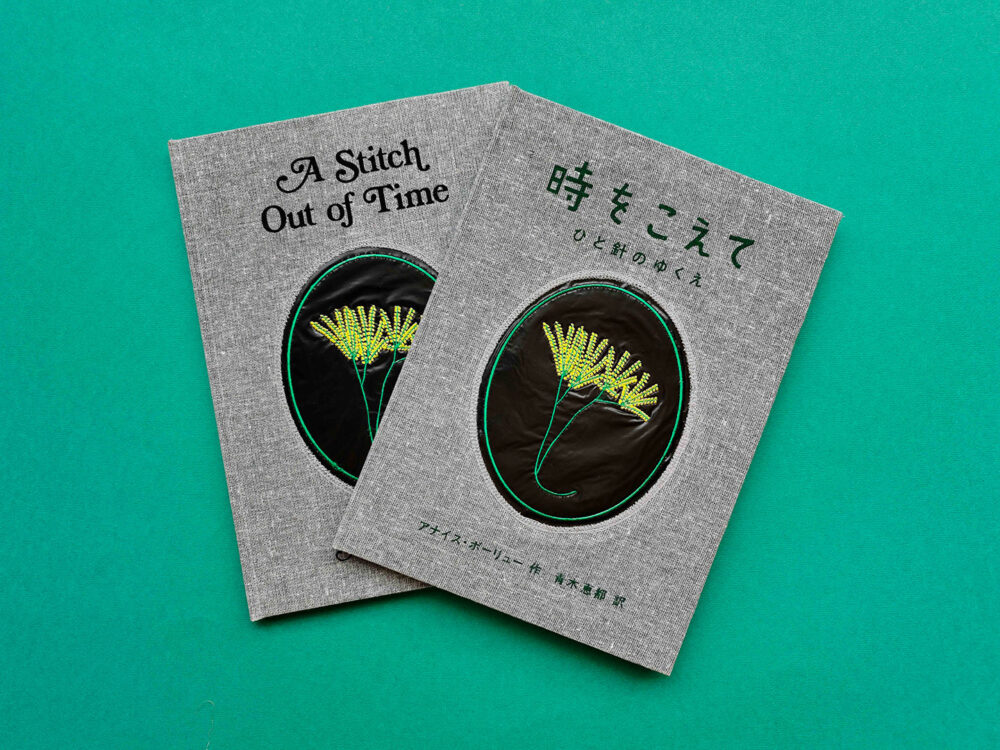

It is with this idea of a planetary garden that I would like to end. Because if we set the scene again — France is the country where I was born and where I live, Italy is the country where I met Gita Wolf, Burkina Faso is the country where I was inspired to embroider on plastic bags, India is the country where Tara Books is, and Japan is the country where Tara Books sowed the seeds of a Japanese co-edition with the publisher Tamura-Do.

A Stitch Out of Time, in English and Japanese

Like a plant, this book has taken time to grow and mature. Starting from the image of one plant, it has turned into an herbarium containing the stories of many. Ultimately, the book has become its own species, perhaps a vagrant, growing beyond its usual range.

Even by our adventurous standards, this book was a production nightmare. Anaïs has described how the idea for the cover evolved: a piece of plastic, individually embroidered with an endangered plant. The idea looked fabulous on screen, but to assemble it with physical material was arduous in the extreme — sourcing the perfect textile for binding, die-cutting the ‘frame’ for the embroidery, pasting the cover together with minute exactitude, screen-printing the title… It took months of experimentation to achieve the level of perfection we were looking for, especially since each piece had to be made by hand, and imperfections were inevitable. In the event, the cover of A Stitch Out of Time has turned out to be exquisite: it looks lovely, but its tactile beauty is best experienced by running a hand over the front and feeling the textures of the textile cover, the smooth plastic insert and the raised threads of the embroidery.

– Gita Wolf

French artist Anaïs Beaulieu learnt the craft of embroidery from her grandmother, a practice passed on through multiple generations of women in her family. After studying at Arts Décoratifs de Limoges, Anaïs worked as a bookbinder for several years where she developed an interest in children’s books and art education. She explored these in her seven years with the celebrated publishing house Les Trois Ourses. Anaïs’ work is also informed by her travels, especially in Africa, which strengthened her interest in craft and the links it can create between people. It was also here that she resumed her childhood love for embroidery, and where the idea for this book was germinated. She now lives and works in Montreuil.

Photograph of Anaïs Beaulieu credit: Barbara Rigon

No Comments