14 Feb The Cloth of the Mother Goddess – From Ritual Art to Cloth Book

By Gita Wolf

New Edition

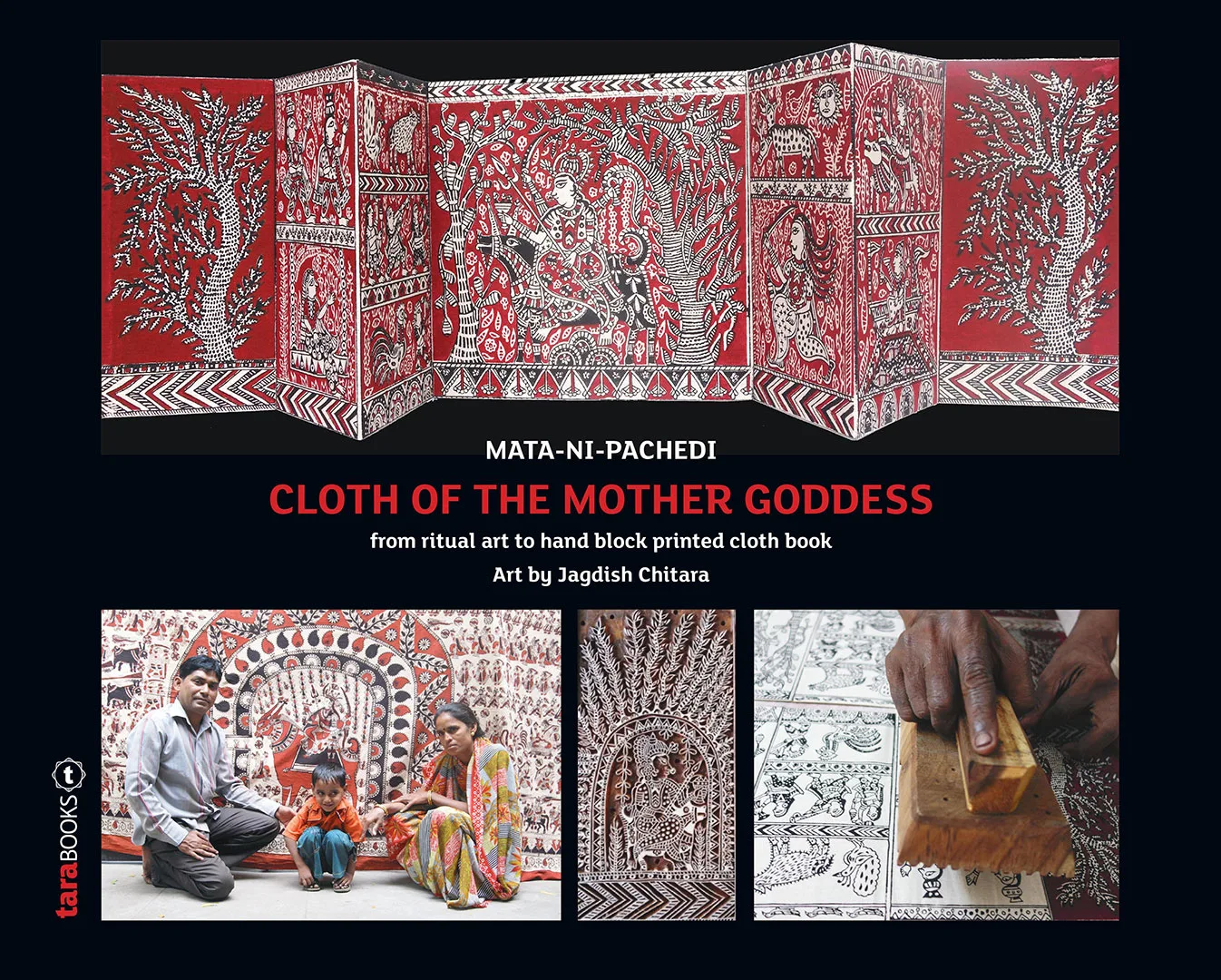

We’re delighted to bring out a new version of The Cloth of the Mother Goddess, an experimental textile book we first published in 2015. It is a recreation of a traditional votive cloth from Gujarat — called Mata-Ni-Pachedi or the ‘Cloth of the Mother Goddess’ — a textile shrine that invokes the goddess. The goddess features in different guises in these shrines, and each has her distinctive divine and human retinue. Believers offer these cloths with images of their guardian goddess to herself… Gifting a piece of creation to the creator is considered the highest form of worship. This is a belief that resonates with artists from other traditions, such as the Rathwa painters who depict the god Pithora and his entourage in their art.

The textile book-shrine

On the main panel of this textile book, is the Mother Goddess, the central figure in the original art form, and she is placed within a grid evoking the architecture of temple doors and alcoves. She is surrounded by attendant gods and goddesses, along with their animal companions, each of whom have their own myths and stories. As is the case in many Indian indigenous art traditions, everything is represented together and sequential events in the story appear to happen at the same time.

When the book is turned around, the panels on the reverse side tell the story of how the Mother Goddess came to be honoured in this form. The narrative here is sequential, and the events happen one after the other, over a period of time. This hand block printed book, familiar to some readers from the first edition, remains unchanged.

Storyboard with narrative

We have retained the paper storyboard for this edition as well. This is a replica of the cloth book, except that additionally, there are text panels which accompany the images. The sequential reverse side narrates in detail how and why the cloth is painted: human beings forget to paint and honour the Goddess, only to have ill luck befall them. Things are finally set right when the image of the Mother Goddess is re-made, and given as an offering to herself.

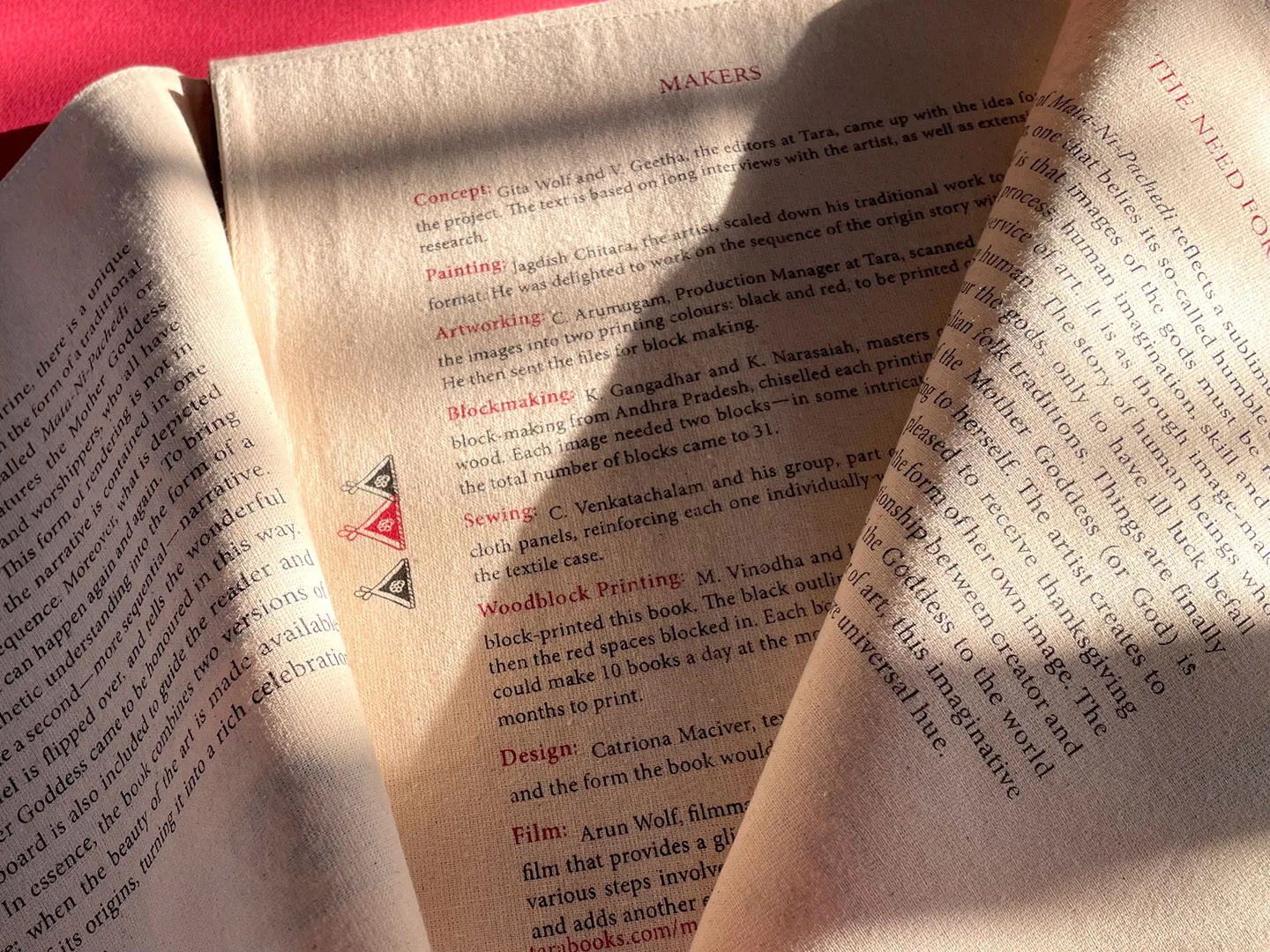

Informational booklet that accompanied the first edition

Like the previous one, this edition too comes with additional information about the art form, the artist, and the making processes. In the earlier version, all of this was presented in a booklet.

Opening the new edition

But we have since re-designed these information sections — they have been silkscreen-printed onto a multi-panel cross-shaped cloth. The reader can unfold this screen printed cloth, and read each of these folds, as one would read a page in a book. Taken together the text on the different folds makes for a layered narrative, which reveals, in turn, the context, process and labour that have gone into the creation of this book.

Layers of information

Revisiting select older projects in this way is a great learning exercise for us as publishers and the interesting question always is: if we were to bring out a particular book today, what would we do differently? When we published the first edition of this book, it broke completely new ground, even by our own adventurous standards. Creating a textile book was in itself a huge challenge. But even as we were working on the production, we were clear that we wanted it to be more than a beautiful object. We wanted the reader to get a sense of the integrity and essence of the original tradition, even as the book created new meanings.

We had paid our tribute to the art, in the form of the textile shrine, and we were happy with what we had done. But we were not sure about the way we had sought to communicate the context around the art. We have always found it important to anchor our projects — particularly those that involve the traditional arts — in a social and aesthetic sense, for our readers. The booklet had served that purpose but we wanted to improve on it. We wanted to come up with a form of communication that was integral to the art form – and after months of experimentation came up with the idea of the cloth wrap.

The Tradition

Artist Jagdish Chitara

We had been working with Jagdish Chitara, the traditional artist who painted the images for this book, on a few projects, when the idea of invoking his original art form came up. Jagdish belongs to a community of textile artisans known as Vaghari. They were originally nomads who moved along the Sabarmati river in Gujarat and specialised in creating ritual textiles invoking the Mother Goddess. Vaghari artisans made this votive cloth, for a clientele who were often as marginalised and impoverished as themselves — being worshippers from so-called outcaste groups. Barred from entering temples, they offer instead a painted image of their particular guardian goddess to herself. Sometimes, the cloth, also called the Chambarvo textile, is also draped to form a temporary shrine. At once an offering and a ‘place’ of worship, this piece of fabric is a poignant symbol of a practice that is a prayer as well as an act of thanksgiving. Its ritual function has persisted to this day and we were moved by its history and meaning.

An original Mata-Ni-Pachedi textile

The tradition appears to go back around 300 years. The cotton fabrics were originally painted and later came to be block-printed. They are then washed in the river waters, and painstakingly dyed with natural pigments. Although some of the materials used for creating the cloth have changed with time, these beautiful swathes of fabric continue to be made using the distinctive colour palette of red, black and white.

Detail from a Mata-Ni-Pachedi textile

The Mother Goddess can be represented in the form of different deities. Each community has their own guardian goddess, with her own particular myths and attributes. The cloth is given as an offering during festivals, the most important of them being Navaratri, or the Festival of Nine Nights, where nine goddesses believed to be incarnations of the powerful and popular goddess Durga are worshipped.

The artist’s home in Ahmedabad, Gujarat

Although the Vaghari’s way of life has changed — many of them, like Jagdish, now live in towns and cities — they still create the traditional sacred cloth. While the number of practising artisans has dwindled, those who have kept with the tradition continue to use almost the same method and style to produce the cloth, a process that has been passed on from generation to generation. The blocks used by ancestors to make the cloth are prized possessions kept within the family.

(L) Artist Jagdish Chitara block-printing, (R) A collection of his wooden blocks

Film

The various steps involved in the remarkable process of creating a Mata-Ni-Pachedi are truly fascinating: to trace the important ones and understand what it involves, we visited Jagdish Chitara and came up with a short film that provides a glimpse into the artist and his tradition.

New Contexts

Book release invitation

Despite their extraordinary skill and imagination, we discovered that most Vaghari artists continue to be impoverished, though some of them, like Jagdish, have begun to use their skills in other ways. He sells secular versions of Mata-Ni-Pachedi, as fabric art. Like other artists, he also creates work that would appeal to a middle-class clientele — from textile and paper paintings to decorative homeware — which allows him access to a small craft market and a modest additional income. In spite of all this, sadly, the social status of Vaghari artists has not changed very much. This has to do with the fact that in caste society, the low social status ascribed to the patrons of Mata-Ni-Pachedi also extends to the artists who create them, and by implication, to the art itself. Historically, in India, artisanal labour and the art forms associated with it are considered high or low depending on the status of the practitioners. The fact that artisans have gone on to create work that is new or beyond a traditional or caste function has not mattered very much.

The Book

Editors Gita Wolf and V. Geetha at work with Jagdish Chitara

This deeply ingrained notion needs to be questioned, so when we invited Jagdish to work with us, one of our aims was to create, along with him, a new context for the reception of his tradition. We wanted to showcase not only the beauty of the original art form, but also tell the story of how it all came to be. That is what a book does best, and this narrative movement is what turns a ritual art object into a book. We were also keen to highlight the sophisticated conception of art that the Mata-Ni-Pachedi tradition upholds, which belies its so-called humble origins: it implies that image-making is fundamental to being human. The underlying belief is that the gods must be re-created periodically, and in the process, human imagination, skill and labour are rekindled in the service of art.

Form, Material and Labour

Block-printing the panels in layers

The connection of skill and labour to art making has always interested us. We’re curious not only about the aesthetic and philosophical aspects of traditional art, but equally in its connection to artisanal practices, the craft that goes into giving it a physical form. In the case of Mata-Ni-Pachedi, this involves painting, block-printing and dyeing techniques which are painstaking, requiring skill and experience. This kind of artisanal knowledge is profound and priceless, but it is not valued highly, and seen more as a sequence of repetitive tasks learned through apprenticeship. Instead of holding artisanal practices against the mirror of industrial manufacture — or seeing them as distinct from art-making — we’d like to connect them intrinsically to the creative process. To make something — to turn ideas and inspiration into material — requires not only imagination, but time, skill and labour.

In a sense, The Cloth of the Mother Goddess book itself is a testament to this long process, and metaphorically speaking, echoes the making of the votive textile.

Sewing the textile wrapping

The book is thus a celebration of Indian artisanal skills. There were a number of creative people involved, at every stage of the process, and we would like to extend all credit to them. They actually sewed together the pieces for each book by hand, created special wooden printing blocks for every spread, and finally hand block-printed the book. We’d like the contemporary reader to appreciate the craft involved in the making of each one of them, so each book is numbered. Every copy is an original, so to speak, and it is the subtle variations and slight imperfections which make it unique.

Design and Communication

There is admittedly a lot that a reader needs to take in, to truly understand and appreciate this book project in all its complexity. From the beginning, we struggled with the problem of how to communicate this, without taking away from the actual book. We settled in the first instance on putting together a storyboard (that annotated the images) booklet (which contained information on the art and its making) and DVD (with a film on the artist at work), along with the book. Even so, there were two issues which continued to niggle at us: the first was the hierarchy of reading. In what order would the reader make sense of the book and all the additional material? And secondly, how was all this material to be packaged together? After some experimentation, we decided to go with a screen-printed cardboard slipcase.

The first edition came with a storyboard, booklet and cardboard sleeve

However, from the perspective of design and publishing, we continued to remain dissatisfied, determined to find better options when the time came for a reprint.

That time has now come, at last, and we’re glad to say that there have been some good developments at our end, both in terms of design thinking and in production. It started a couple of years ago, when Tara was invited to hold a series of exhibitions in Japan, and we had the opportunity to travel there.

The Cloth of the Mother Goddess on display at the Itabashi Museum in Japan.

Photo courtesy: Kodai Matsuoka

We were particularly fascinated by the fine design and craft traditions we got to know in Japan, and returned with several ideas we wanted to try out. The inspiration for the cloth panel wrapping for The Cloth of the Mother Goddess book owes its genesis to Japanese traditions of book wrapping. The information from the booklet has been edited down to fit the fold of the cross-like cloth, and can be read in any order when the folds are opened out. Producing this cloth cover was the next hurdle, but meanwhile, we had more means at our disposal.

The redesigned wrapping holds together the book and storyboard

A year ago, we also decided to start a small tailoring workshop together with Studio Tolsta, a textile craft unit run by one of our designers. Called Tuni, the workshop allows us to experiment with textiles as material in the making of books, and we have several projects on hand. Among other things, we will be packaging our handmade books in bespoke reusable cloth covers, and phase out their plastic wrapping.

Making the bespoke voile cover

Having this kind of in-house expertise has been a game changer, and once the cloth cover design was in place, we were confident of producing them in larger numbers. We think the results speak for themselves. It’s always gratifying, as a publisher, to have a chance to reimagine favourite projects and take them up another level.

The new edition in its reusable cover

Makers

Gita Wolf started Tara Books, as an independent publishing house based in India. An original and creative voice in contemporary Indian publishing, Gita Wolf is known for her interest in exploring and experimenting with the form of the book and has written over twenty books for children and adults. Several have won major international awards and been translated into multiple languages.

V. Geetha is a writer, translator, social historian, activist, and a freelance editor and a leading intellectual from Tamil Nadu, India. She has been active in the Indian women’s movement since 1988, organizing workshops and conferences. Geetha has written widely, both in Tamil and English, on gender, popular culture, caste, and politics.

Jagdish Chitara is a highly skilled artist who lives in Ahmedabad, and works in the Mata-Ni-Pachedi style of ritual textile painting. He has been practising for over 40 years, having learnt this ancestral craft from his father and grandfather. The tradition has been kept alive and passed on through at least four generations, and Jagdish has inherited nearly 300 wooden blocks from his ancestors. His own immediate family assists him with his pieces. There are now around 50 artists who practise this art, including many who belong to Jagdish’s father’s generation. Jagdish himself is one of the best-known artists from this tradition, and has participated in various government-run workshops and fairs within India. He has exhibited his works at the Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya in Bhopal and in cities such as Mysore and Raipur; his works have been bought by art lovers in India and abroad. This is Jagdish’s third collaboration with Tara Books; he also illustrated The Great Race and the forthcoming title, Brer Rabbit Retold.

C. Arumugam is the Head of Production at Tara Books. Initially a theater actor, he started his screen-printing career printing visiting cards from home as a source of extra income. Soon he came to be known for his excellent quality of work and his screen-printing career grew into a full-time job. He has worked with Tara Books since their very first project and has since gained a great level of expertise in many modes of printing including: offset-printing, letterpress-printing and currently, Riso-printing. He now runs a fair-trade residential printing workshop of 18 people and has been integral in pioneering the process of making affordable, artist’s books made completely by hand.

The Kondra brothers — K. Gangadhar and K. Narasaiah — from Andhra Pradesh belong to a family of traditional wooden block-making artists. They were initiated into this art by their uncle when they were teenagers. After nearly 35 years, they now run a block-making workshop with a team of 7 skilled artisans in Machilipatnam, Andhra Pradesh. Their craft demands patience, steadiness and an eye for intricate detail; and the Kondra brothers are known to be among the most skilled in the country. In 2002, the brothers jointly received the National Award from the Ministry of Textiles for craftsmanship in Wooden Block-Making. They have exhibited their works in India, UAE, Mexico and Australia.

C. Venkatachalam was born and brought up in the village of Alankuppam, Pondicherry Dist. After completing his high school, he went on to learn tailoring at the Pondicherry Institute of Tailoring. Starting as an apprentice helper at the age of 17, he became a cutting master, going on to work with fashion designers and upcycling projects in Auroville and Pondicherry.

AMM Screens was established in 1995 by C. Arumugam to screen-print copies of Tara’s first handmade title, The Very Hungry Lion. What started as a small workshop with 7 people, has grown to employ 18 bookmaking artisans. The workshop has evolved over the years and it has been guided by experimentation, innovation and an openness to pushing the boundaries of book-craft. Today, the artisans work not only with silkscreen-printing but also with letterpress-printing, Risography and wooden block-printing.

Catriona Maciver is a multidisciplinary designer from Scotland. After graduating in Graphic Design from Central Saint Martins College in London, she travelled to India to explore traditional artisanal craft and culture. It was this interest that led her to work for Tara Books in 2013. Catriona now lives in Chennai and runs Studio Tolsta, a product and textile company specialising in contemporary handcrafted homewares and travel goods.

Arun Wolf has been associated with Tara Books for several years, and has worn many hats (not literally) in this time including filmmaker, editor, web and business development. He has a keen interest in the intersections between culture, politics and commerce, particularly in craft process and art practices of individuals and communities that exist on the margins of the mainstream. He enjoys working on cross-media projects that tell compelling stories by bringing together different mediums.

No Comments